The basic structure described in the previous section allowed inland communities to have access, for example, to seashells, despite the fact they might never have seen the ocean themselves. However, one may ask: how is it that the people of Papua were still trading with stone axes in the 20th century? Even more so if the reader knows that Papua might be the oldest place on the planet where agriculture was developed, with some estimates suggesting that root vegetables were cultivated at least 10,000 years ago—slightly earlier than the domestication of grains in the Fertile Crescent.

That is actually a question Yali, an exceptional politician from Papua, asked Jared Diamond in 1972 when he was conducting fieldwork there to study ornithology, including birds such as the bowerbird. The actual question was: “Why do you white people have so much cargo and bring it to Papua, but we natives have so little of our own cargo?”—summarised as: “Why do your people have so many things compared to us?” For Yali, cargo was the generic term for all the items Westerners had brought to Papua since World War II. He was, in fact, asking about the technological gap between the Westerners travelling there and the local people.

Diamond spent 30 years developing an answer, culminating in his book Guns, Germs and Steel. In it, he presents two main theses:

First, geographically, some populations had more access to natural resources to begin with, such as plants and animals that were easy to domesticate. For instance, in Papua, the largest domesticable animal was the pig, while in Eurasia and Africa, cattle have symbolised wealth and power for generations. Papua also had no access to grain, while civilisations like the Mayas domesticated maize. Despite not having large animals, that was sufficient to develop a thriving and complex civilisation with many types of “cargo”. Additionally, domestic animals made human populations more exposed to germs, which they gradually adapted to. However, when these naturally engineered biological weapons encountered previously isolated populations, they wiped out 90 to 99% of the locals in less than a century. The pigs kept by Papuans may have spared them a similar fate to that of the Americas and the distant Pacific Islands.

The second thesis is that, due to geography, some areas of the world were better connected than others. Again, Diamond argued that it was relatively easy for trade networks to span Eurasia and Africa, with goods, ideas, domesticated foods, technologies, and ideologies spreading far in just a few generations. This was especially true for crops; species domesticated in one location often had suitable growing conditions across the climate zones from the Iberian Peninsula to Japan. This did not occur in other regions, such as the Americas, where many similar technologies had to be independently developed by both the Mesoamerican and Andean peoples. Their centres of domestication were only a few thousand kilometres apart. However, both groups had to independently domesticate crops like maize, cotton, and beans. Moreover, useful animals like the llama and crops like the potato, domesticated in the Andes, never reached the Mayas, while the writing system developed by the Mayas never made it to the Andes. According to Diamond, these gaps are due to difficult and diverse geographies. There is no easy land route connecting these American regions—dense tropical jungles, vast swamps, and rugged mountain ranges with dramatically different climates hinder the spread of domesticated species. Even today, in the 21st century, there is no road connecting these two areas. The Darién region, on the border between Panama and Colombia, remains impassable by vehicle, making it the only place on the continent without a road from north to south.

With these two main theses and strong reasoning, Diamond makes his case to answer Yali’s question. According to him, Papua did not have the species or connections that benefitted Europeans upon arrival. Europeans were simply lucky and thus came to dominate the known world. That left Papuans with a relatively limited set of food sources and restricted access to technologies developed elsewhere.

This view has been widely debated and does not fully account for the timing of major expansionist events. Still, the picture Diamond paints holds reasonably well until the 16th–17th centuries and the largest biological genocide in human history. Afterwards, the situation becomes more nuanced, as the connectivity of the world began to increase exponentially—but we will explore this in another chapter.

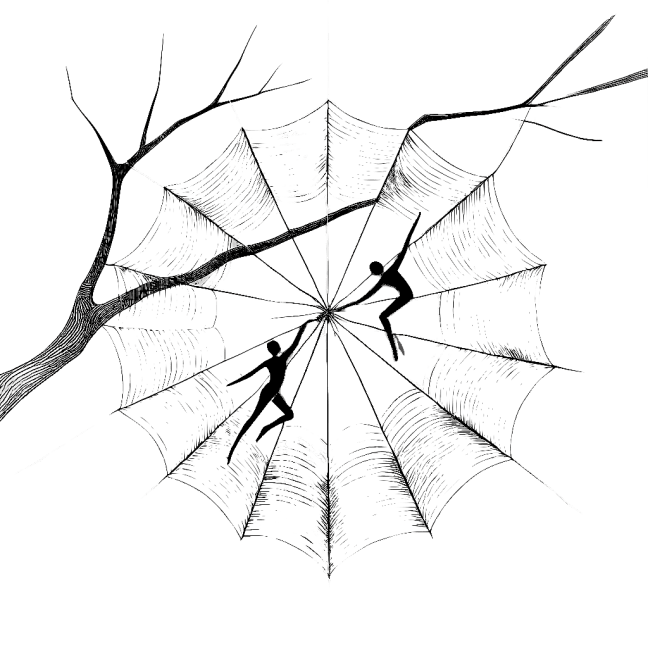

The limitation on access to technologies and information for the Papuans is related to our earlier examples of basic trading networks. These can only extend as far as humans can reliably reach each other at a more or less consistent pace. If mountains, oceans, and jungles must be traversed, the task may be too dangerous or uncertain to attempt. In such cases, communities at each end remain isolated. On the other hand, if obstacles are surmountable and there is a desire to connect, these networks can transform the well-being of participants. This is the case with the Eurasian and Indian Ocean trade networks. These spanned over 2,000 years, bringing silk, gunpowder, spices, and paper westward, and silver and wool eastward. Or take the so-called Columbian Exchange, where Europe plundered the immense wealth of the Americas, borrowed some botanical knowledge and cultural inspirations, and in turn colonised and Christianised native populations, erasing or warping their lands, traditions, institutions, and knowledge systems.

Returning to our earlier examples and thought experiments, these scenarios depicted only weakly connected communities. For instance, fragmented travel and exchange networks were the norm in the Papuan highlands. Although goods like axes or shells could travel freely, people could not. Residents of a group traditionally could not travel far beyond their territories or their closest trading partners. Unannounced or long-distance travel posed great risks—aggression, even death—making lone long-distance trade virtually non-existent. Commerce beyond immediate neighbours was carried out by intermediaries. Each of these intermediaries usually took a cut or incurred costs, inflating the final price of the item. This inflation could only go so far—only items of high value or buyers with considerable resources could justify the costs. This effectively limited how far an object could travel and placed natural boundaries on the kind of connection network described in the previous section. This is comparable today to drug or wildlife trafficking, where lightweight, high-value items traverse vast regulatory and law enforcement hurdles over thousands of kilometres.

Conversely, if exchange links are too weak or complex, they may collapse shortly after forming—before significant transfers of goods, ideas, or technologies can occur. This has happened countless times across different regions and eras. Think of a group of friends that never fully bonds, or a business that cannot reach its customers. Let’s consider some more striking historical examples. At least twice before Columbus, people from faraway regions reached the Americas, but failed to establish lasting presence or strong cultural exchange.

You might be thinking of one such example: the Vikings from Scandinavia in the 11th century. They arrived from sparsely populated Greenland, but their colonisation efforts in Vinland (modern-day North America) failed. Without delving too deeply into why, it’s clear they had the means to reach distant shores and found good land, but not much more. The distances were vast, the local resources were not especially valuable, the natives were not always welcoming—possibly becoming infected or hostile—and the Vikings had limited capacity for sustained support. Climate and political factors played a role, but ultimately the venture proved too costly for too little return.

The second example is even more epic and deserves wider recognition: the Polynesian crossing of the Pacific Ocean to reach the coast of South America. Sadly, we lack written records—like the Vinland Sagas—or significant archaeological evidence. But through genetic, linguistic, and species transfer evidence, we know that about 800 years ago, seafarers from the Polynesian islands reached South America. For context, that’s more than twice the distance Columbus travelled—and his crew believed land awaited. It’s also more than three times the longest Viking sea crossing to reach the Americas. The Polynesians had no clear reason to expect a continent ahead, yet they sailed into the unknown.

Imagine being in a boat no more than 30 metres long and about one metre wide, possibly connected to another boat as a catamaran. This platform allowed a few dozen people to bring animals, water, and supplies across the vast ocean. Some examples of these vessels—such as Druas in Fiji—could carry more than 200 people. Now imagine that your only known geography was a scattering of islands, and you did not know where or if more land existed. Countless such expeditions must have failed before one succeeded in making the 6,000 km journey—until finally, they found an enormous continent. Then they had to sail back, locating tiny home islands amid the ocean after weeks at sea. The adventure, mindset, skill, and ultimate success—after who knows how many failures—is one of the most remarkable, untold stories of human exploration.

This is not comparable with the Viking or Iberian voyages across the Atlantic. Those sailors knew something awaited beyond. The Vikings had seen driftwood from the west wash ashore in Greenland. Columbus, though mistaken in his estimation of the world’s size, expected land. The Portuguese, too, found driftwood in the newly colonised Cape Verde islands—Paubrasilia, or “firewood”, due to its red colour—which gave Brazil its name. All these peoples had reasons to expect land in the west.

We know Polynesians completed this journey because they brought coconuts and chickens with them—and brought back sweet potatoes, which later spread across the Pacific islands as a staple crop supporting larger populations. They also had children with local peoples, leaving genes still found today in Mesoamerican and Mapuche populations. There is even evidence of American ancestry in Polynesian populations.

This widespread gene flow shows that Polynesians not only crossed the ocean more than once but established contact across a broad swathe of the Pacific coast of the Americas. Unfortunately, the contact was not maintained over time, and no further instances of intermarriage are evident after 1300 CE. Furthermore, Polynesian navigational technology was not passed on to the local peoples. Native Americans would have greatly benefitted from such skills—especially considering the lack of transport links between North and South America even today.

We can speculate why the contact faded and the technology was not adopted—unlike sweet potatoes. In a simplified view, the connection was likely too distant and involved too few people to become meaningful. Perhaps the Marquesas Islands had only a few hundred inhabitants at the time, while the continent had millions and two sophisticated civilisations that saw little value in these distant seafarers. Whatever the case, the exchange was short-lived and limited.

More complex reasons could also explain the lack of adoption. For instance, Austronesian sailors from Makassar routinely travelled to the northeast coast of present-day Australia—around 3,000 km away—to harvest sea cucumbers for the Chinese market. This trade continued for centuries, ending only in the 20th century due to Australian colonial restrictions. Although contact endured, no lasting colonies were established, and the mixed communities that emerged never thrived. Some wives were exchanged, and a basic trade language developed, but local people only adopted simple technologies such as dugout canoes and shovel-nosed spears. More advanced knowledge may not have been shared—or perhaps locals weren’t interested.

Similar patterns emerged with Austronesian expansion to Madagascar and Taiwan. Though close to the mainland, these regions show little lasting influence on nearby East Africa or Southeast Asia. This suggests that Austronesians successfully expanded to uninhabited or sparsely populated areas (e.g. Pacific islands, Madagascar), but failed to make inroads in already densely populated regions like Asia, Africa, Papua, or the Americas.

In Australia’s case, the issue might have been resource scarcity. Northern Australia may not have offered enough to entice settlers. Local people may not have seen value in adopting agriculture or foreign technologies. Additionally, complex knowledge like seafaring is often guarded. Sailing is more than boat-building—it involves reading stars, winds, currents, and more. Mastery takes time, risk, and community effort. If local life was already sufficient, why go to the trouble?

Moreover, the fact that sea cucumber expeditions were male-dominated may have prevented the creation of Austronesian communities in Australia.

A good related example, but limited to technology and infrastructure, is the first transatlantic telegram cable. It was build in 1856 and it only worked poorly for 3 weeks until it completely failed. It took 15 years to build the successful 2nd cable. In this case a combination of affordability, technological improvement and willingness to communicate more instantly two continents made the 2nd attempt stuck. Now we have tens of thousands of underwater cables connecting all continents to transfer high speed data. But we could imagine many scenarios in which after the first failed transatlantic cable, the trend did not continue.

From the cases outlined here, we can see how many different scenarios could limit cultural and technological exchange, creating a nuanced and often unpredictable picture. Establishing sustained connections across natural and cultural boundaries is a long, fragile process—often with little success on the first attempt.

Previous

Next

One thought on “Fragile communication”