To understand the networks that can establish this project’s question, it would be interesting to reflect on how such networks were created. And for that, one has to reflect on the dominance of the planet by the Western European powers by the end of the 19th century. This dominion, as described before, started with the parallel events of the arrival in the Americas, wiping out about 90% of their pre-contact population, and conquering Malacca after the circumnavigation of Africa. These two events were achieved by two small powers, inhabiting a medium-sized peninsula at the end of the Earth (Finisterre, the end of the land, is in Galicia, north of Portugal). The peninsula lies between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic and was shared with two more kingdoms, Navarra and Aragon, which did not participate in these events. Other Atlantic-facing small powers soon joined the party, with France, the Netherlands and England taking over the lion’s share the century after, and some other colonising efforts conducted by Denmark, Scotland, and even Poland. Once Germany and Italy were created, they eagerly jumped into the “game” as colonial administrators. But beyond the administrations, emigrant European populations, mostly from the western and central portions—but in reality from all over—had huge influences all over the world. And last but not least, Russia, which still holds its colonial land-based empire, conducted overland the same land conquests that the rest of the powers were conducting over the oceans.

To see the effect that about 10 nation-states had over the world, you can go to the modern world political map and start crossing over the countries and territories that at some point fell under their control, be it nominal or real, where they had actual power in deciding much of their political and economic actions.

All the “New World”—i.e. America—fell under the actual or nominal control of these states or their post-independence nations controlled by European elites.

In Africa, with the exception of present-day Ethiopia (which was occupied for 4–5 years under Fascist Italy), the entire continent was nominally under the control of the Western European nations by the end of the 19th century. The African continent’s political map now bears the scars of that colonisation in the form of the terrible borders left over by the Europeans, which still today force historically antagonistic communities to share a state, while others that were historically unified are now split by an invisible line.

Oceania was swept away by the Europeans, with the Kingdom of Hawaii—one of the last remaining independent archipelagos—losing its sovereignty and most of its population to the US by the end of the 19th century.

In Asia, Portuguese, Dutch, English, French and Russian powers took over most of the land. Only six sovereign administrations were never actually controlled by the Europeans. These were the isolated Japan, large parts of mighty China, Thailand, Afghanistan, Persia (now called Iran), and the Arabian desert now controlled by the Saudis. It is debatable whether the Asian Ottoman Empire controlled parts of Europe, or the European Ottoman Empire controlled parts of Asia, but whichever it is, it had strong European influence in its administration, which can still be seen in modern Turkey. However, unlike Russia, Ottoman rulers did not intermarry with the rest of European aristocracy, in part limiting European influences in the ruling class. Other territories not controlled by the Europeans include Mongolia, which was under Qing Chinese dynastic control and then briefly independent as a puppet state under Soviet influence. Similarly, the two Koreas were under Chinese and then Japanese dominion and colonisation, and then divided in two—with the US influencing the South, and the Soviet Union and China influencing the North. The British had a mixed dominion policy. Oman (with Muscat being a Portuguese trading colony) formerly controlled great parts of the coast of present-day Tanzania due to its lucrative slave trade; that control was destroyed by the British, who then took over most of Oman’s government and internal affairs until the 1970s. Similarly, other sovereign lands—like Bhutan, Nepal, many Indian kingdoms, and Oman—at one point or another left their external political affairs and some internal ones in the hands of the British. Finally, Japan began imitating the European powers and took colonial control over Korea and large parts of China, even creating a puppet state called Manchukuo in Manchu lands in China’s northeast.

For these seven or eight places on the map that can be painted as outside direct colonial control, each suffered, to some extent, imperial influence. Saudi Arabia was mostly empty desert land with few resources until the discovery of oil, and its existence is linked to British foreign policy—to create a Saudi force as a counter-power to the Ottoman Empire at the end of the 19th century. Iran was divided into spheres of influence by the Russians and British, and its modern borders were mostly decided by them. For Afghanistan, its borders were drawn by the British and the Russians, including the strange northeastern “corridor,” which was made the width of the most powerful cannons at the time, so that British and Russian artillery could not shoot each other over Afghan territory. Most of Afghanistan’s external political affairs were controlled by the British. Thailand suffered a similar fate; being between French and British-controlled territories, it was used as a buffer state. The British and the French drew its current borders and split the country into spheres of influence, as in Iran. China was defeated first by the British, and then by a coalition of the British, French, Russians, US, Japanese, and Germans. Though they did not take full control, the British strongly influenced China’s foreign policy for decades, and China was divided into spheres of influence. Japan won several wars against Chinese administrations and took control over large parts of the land before the end of WWII. Japan itself was forced to open its borders and commerce to foreign powers when Tokyo was bombarded by a US armada in the late 19th century, and later—after some mushroom-shaped explosions—was occupied by the US and the British. It was forced to adopt an army for self-defence only and to remain aligned with US interests.

Antarctica was claimed only by European nations, and the Antarctic Treaty, which theoretically reserves these lands for all humanity, was drawn and signed by six European nations. Currently, most of the scientific bases that exist there are European ones.

Out of the roughly 200 sovereign administrations now covering the land masses of the Earth, plus Antarctica, only about seven or eight experienced little direct control by European powers. This simple map illustrates the extent to which European powers exerted near-global influence over the planet 100 years ago. Even today, of these eight territories, only Japan, China, Saudi Arabia and Iran can be said to have—or have had—notable autonomy and influence beyond their borders. Turkey may also be included, depending on which continental perspective is used. Therefore, the world remains dominated by European nations and their administrative legacies. Alternative sovereign administrations with global influence emerge only from four or five distinct cultural backgrounds. These numbers highlight how five Western European nations, and one Eastern European one, took over most of the world.

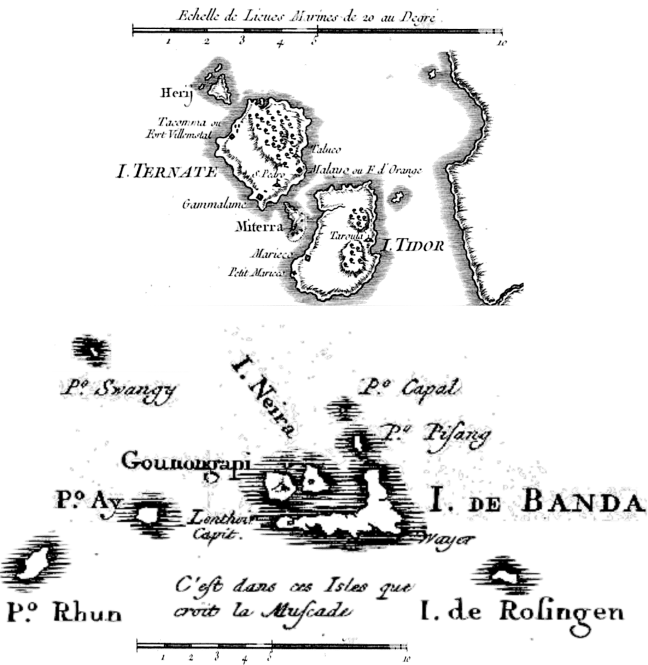

To illustrate how the Europeans went about conquering the world, let’s go back to the spice islands. The interaction between three European powers and three native sovereign powers provides three different examples of forms of dominion: by annihilation, by trade, or by playing European powers against each other. We can centre the native powers in the two islands of Tidore and Ternate, and the Banda archipelago. Similarly, we can focus on Portugal, Spain, and the Netherlands as the three European powers. As we have seen, the lucrative trade in the spice islands centred on cloves, mace, and nutmeg. Cloves are the dried flowers of a tropical tree found only in Tidore and Ternate (and some other nearby islands). Nutmeg and mace are inside the seeds of another tree, which was only present in the Banda archipelago.

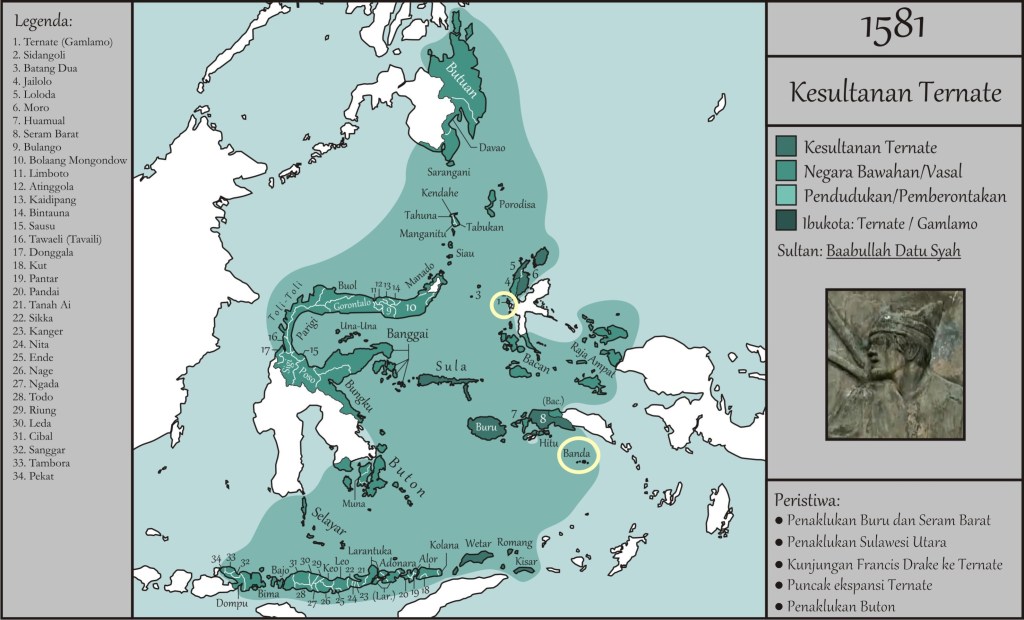

As described, Tidore and Ternate are two small volcanic islands neighbouring each other at a distance of less than two kilometres. To this day, both have rival sultans. At the time of the Portuguese and Spanish arrival, each controlled its respective island and the cloves trade, plus claimed rival control of most lands east of them, all the way to western Papua. Perhaps luckily for them, the Portuguese allied with the Ternate sultanate, while the Spanish soon after allied with the Tidore one. These two sultanates had been long-term neighbouring rivals, but also intermarried, not unlike the Spanish and Portuguese aristocracies. The European powers never conquered the sultanates, although they allied with them and built forts on their territories. The Ternateans were able to expel the Portuguese after a few decades. The Tidoreans used the Spanish as convenient allies against the Ternateans.

Things became more complicated after the Dutch East India Company (VOC, founded in 1602 and with authority to declare wars!) took over the nearby Banda islands (Ambon), home to mace and nutmeg.

Soon after, the Ternateans placed themselves under Dutch influence to fend off the Tidoreans allied with the Spanish, who controlled half the island and even captured the sultan. After the Spanish left the area, the sultan rebelled against the VOC but instead lost independence and came under VOC rule. Ternate became the capital of the Moluccas and the wider Indonesian possessions until the Dutch founded Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1619. Today, Ternate is the capital of the North Maluku province of Indonesia, with a population around 200,000. The sultanate continued until 1975 and has now been restored by the royal family in a ceremonial role.

Meanwhile, the Tidorean aristocracy descended into infighting, ditched the Spanish and allied with the Dutch. The VOC convinced the sultan to eradicate all clove trees in his realm to strengthen their monopoly. In compensation, the VOC gave generous donations to the sultan. With the obvious impoverishment that followed losing control of the spices, Tidorean rebels allied with the British, who soon conquered it. Later, the Dutch took back control of the territory—but not before the British took seeds from the clove trees and began planting them elsewhere, beginning the end of the monopoly. The Tidore sultanate lapsed in 1905 and became a regency, but was revived to counter Indonesian independence claims over West Papua. Today, it holds a ceremonial role in the Indonesian state.

Unlike Tidore and Ternate, the Banda Islands—a small archipelago of a maximum 15.000 inhabitants south of Halmahera—were run by orang kaya, or “rich people”. As said, Banda was the only source of nutmeg and mace. These were sold by Arab traders to the Venetians at exorbitant prices. The Bandanese also traded cloves, bird of paradise feathers, massoi bark medicine, and salves. The Portuguese tried to build a fort in the central island but were expelled by the locals and did not return often, buying nutmeg and mace through intermediaries. Initially, the Bandanese were left to their own affairs, but they were unprotected by any other European powers and their artillery.

By 1609, the VOC arrived. To put it mildly, the Bandanese were not exactly enthusiastic about these slightly different Europeans, who brought only wool and odd Dutch crafts in exchange for a monopoly. Like the Portuguese, the Dutch wanted to build a fort. The Bandanese responded in the best way they could—by ambushing and decapitating the VOC representatives. The VOC retaliated, levelling random villages. In the resulting peace treaty, the Bandanese finally allowed a fort.

Meanwhile, two of the islands, the westernmost ones—sadly named Ai and Run—allied with the British East India Company, who began trading with them. The VOC launched an annihilation campaign, first against Ai (Ay in the opening post map), killing all men, while women and children died fleeing or were enslaved. On Run (Rhun in the opening post map), the natives, with the help of several Englishmen, held out for over four years but ultimately lost. Again, the Dutch killed or enslaved all adult men, exiled the women and children, and chopped down every nutmeg tree to prevent English trade. Run is the famous island that was exchanged for Manhattan (New Amsterdam) in 1667. Incredibly, the British did not replant nutmeg trees elsewhere at the time. They would only do so in 1809, during the Napoleonic Wars, ending the Dutch monopoly and making the tragedy of the Bandanese even more sorrowful.

By 1821, the VOC wanted a renewed monopoly so badly that they decided to annihilate the remaining Bandanese. They assembled an invading force of thousands of Dutch and hundreds of Japanese soldiers and launched it on the islands—then home to only a few thousand people. After a failed peace treaty, the invading commander declared that “about 2,500” inhabitants died “of hunger and misery or by the sword,” and that “a good party of women and children” were taken, with not more than 300 escaping. The original natives were enslaved and forced to teach newcomers about nutmeg and mace agriculture. At the cost of genocide—and facilitated by natural plant endemism—the VOC had a monopoly for about 180 years. The British effortlessly invaded in 1796 and 1808, and this time decided to plant nutmeg trees in another former Dutch colony: modern Sri Lanka.

Sadly, Tidore, Ternate, and the Bandas illustrate the fate of many other European colonial efforts until the 20th century: bare survival by cleverly playing European powers against one another, becoming important administrative centres at the loss of complete autonomy or independence, or facing total annihilation and repopulation of blood-stained lands. Despite these different destinies, the outcome was the same: being utterly dominated by Western European administrative frameworks, as we will see in what follows.

Previous

Next