Olía a orines de mico. 'Así huelen todos los europeos, sobre todo en verano', nos dijo mi padre. 'Es el olor de la civilización'.

She smelled as money piss, that the smell of all Europeans, specially in summer" our father told us "that is the smell of civilization"

Gabriel García Márquez, Doce Cuentos Peregrinos

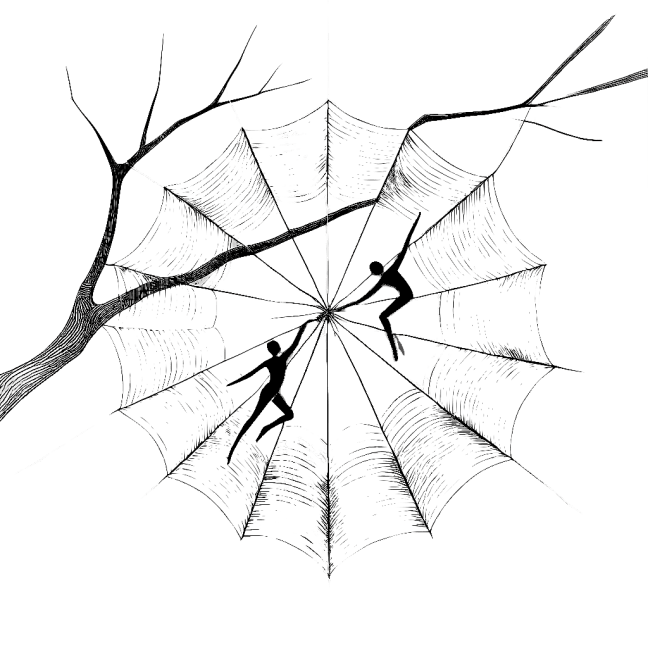

With the previous examples of failed connections, we can see the limits of the system presented earlier—just linking neighbours allows goods to flow only as far as they can be afforded.

The key point we will focus on now—and simplifying immensely complex human relations—is cost versus affordability: who is able to establish and maintain long-distance links that are worth the effort, over long periods of time?

To answer that, we will skip through 320,000 years of history, from the “first hints of exchange” to the onset of globalisation. I will place the beginning of our current globalisation trend at the breakdown of the ocean navigation barrier, accomplished by Western Europeans in the 15th and 16th centuries. In between these two time points—separated by more than 300,000 years—there is the accumulation of regional innovations, the constitution and entrenchment of increasingly diverse networks and hierarchies, which expanded and intensified the use of resources and energy. These “merely” 300,000 years have been widely studied elsewhere, and the reader may be familiar with the traditional “linear” narrative: from hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists, to city-states, to kingdoms, to empires, to nation-states. This image has been widely discredited, as the previous section shows, with many failures and non-linear trends. It has also been demonstrated repeatedly that no group is inherently more “advanced” than another. What people do exceptionally well is adapt to their environments—and the simpler the environment, the more efficient they tend to become. However, across these 300,000 years, there is an unmistakable increase in the scale of connectivity. This reflects episodes of creation and stabilisation of ever more distant networks, as seen in the previous section. These serendipitous mechanisms anchor larger-scale connections and reinforce otherwise fragile or unaffordable links.

So, if you will pardon me for glossing over 300,000 years of history, in the next section I will focus on the integration of all these networks into one worldwide system of connectivity—an unprecedented moment in human history—which leads us to the main question of these writings.

We all know the story of how European societies reached the shores of the Americas, changing the map of the world forever—quite literally, by creating modern mappae mundi and placing Europe at the centre. What you might be less familiar with is why that happened—why did Columbus sail west at that particular time?

Starting with cost versus affordability, we first needed something of high cost—in this case, we can focus on the spice trade. Specifically, the costliest spices were cloves and nutmeg (plus mace—the red aril of the nutmeg seed). Unlike silk, pepper, cinnamon, and ginger (other highly valued goods that travelled long distances), in the 15th century, nutmeg and cloves could only be found in two very small archipelagos the reader may be unfamiliar with. These are Tidore and Ternate for cloves, and the Banda Islands for nutmeg and mace. Today, they are part of Indonesia, in the Maluku Islands area. These spices were highly aromatic and highly valued in European markets, where they arrived in refined forms such as oleoresins, butter, essential oils, and powders. For Europeans, it was impossible to know the exact origin of these spices—some even thought they were of mineral origin. They did indeed come from faraway lands, often erroneously attributed to India, which was a genuine source of cinnamon and pepper. These species had a high cost relative to their volume and therefore represented a strong incentive to bridge the distance between Western Europe and India. In fact, these very spices were the reason Western Europeans—starting with Portugal and Castile—eventually bridged that 14,000-kilometre gap.

But why were these spices so costly, and why did people at the opposite end of the Eurasian continent want them so badly? Nutmeg and cloves had many uses. You may be familiar with their use in recipes—they did enhance the taste of food—but even today, with their lower price, ever-present in European cuisine, unlike other ingredients like tomatoes or potatoes, not present before the European expansion over the world. Another major use of these species was in perfumes. By the 15th century, European hygienic practices had changed significantly. In the 14th century, public baths were common throughout Europe, as it is quite typical for human beings across cultures to enjoy being clean and having clean people around them. However, the Black Death waves of the 14th century caused many bathhouses to close. Though some reopened, European aristocracy had, by then, begun adopting new fashions—such as undergarments and tight-fitting tailoring—which, in turn, created new ways to “trap the body’s evacuations in a layer above the skin”. At the same time, certain strands of the Catholic Church increasingly viewed bathing, nudity, and hygiene as contrary to chastity.

In the Iberian Peninsula, the Christian aristocracy—especially in the north—was gradually reclaiming land from Muslim rulers. Bathing and hygiene were (and still are) highly valued cultural practices in the Muslim world, and often also served as forms of social interaction. Therefore, part of the Christian Iberian aristocracy cemented its identity by rejecting cultural practices closely associated with their Muslim subjects, neighbours, and slaves. All of this led parts of European and Iberian elites to adopt habits that amplified body odour: less bathing, less washing, and tighter clothing. In warmer climates, this likely made body odours more intense. Consequently, rare, expensive, highly perfumed spices could help mask these natural human emissions—while also signalling wealth and status. This helps explain why the Iberian aristocracy, in particular, was motivated to fund direct expeditions to distant lands.

Ironically, Europeans not only brought diseases to the Americas, but also carried American diseases back to the continent. The most infamous of these was syphilis. Once syphilis began ravaging Europe, bathhouses once again closed—this time because baths were associated with libertine behaviour, and syphilis was primarily sexually transmitted. Additionally, beliefs grew that disease could be carried through water, and that open pores (caused by bathing) allowed sickness to enter the body. Within a few decades, bathing had largely disappeared from European daily life. Few households had running water, so opportunities to bathe were almost non-existent. Coupled with aristocratic customs and religious identity-making, this gave rise to figures like Louis XIV, who famously claimed to have bathed only twice in his life.

This cultural environment turned humble botanical species like nutmeg and cloves into commodities capable of financing multi-year expeditions—risky ventures where many ships and sailors might be lost. In the case of the Magellan expedition, only one of five ships completed the circumnavigation—without Magellan himself—but it returned so full of spices (including pepper) that it paid off the entire venture and paved the way for Spanish colonisation of the Philippines. From the association with perfume and the abandonment of bathing, we derive the enduring stereotype that Europeans don’t smell especially pleasant—particularly in summer. That this has anything to do with “civilisation” is now a running joke used by formerly colonised peoples to poke fun at their colonisers—whose domination was often justified on the basis of “cleanliness”.

Let’s now focus on the affordability of finding an alternative route to the spice lands—ultimately disrupting existing sea and overland trade networks by bypassing dozens of intermediaries. The process of making that circumvention possible was itself the result of 300,000 years of innovation, technological development, and skill acquisition. Crucially, as with the Austronesians and Vikings, it was the development of highly reliable navigational skills that enabled this. By the 15th century, Mediterranean and Atlantic ships were sturdy and autonomous enough, and the Iberian Peninsula had become a melting pot of maritime knowledge, making it affordable to attempt reaching India via new routes that bypassed the Levant.

Columbus believed his own (incorrect) computation of the Earth’s diameter—around a third smaller than it actually is—and convinced the Castilian crown to fund his westward voyage to reach “India”. His proposed route was reckless and misguided. But, as previously mentioned, there were hints that land existed across the Atlantic—not so far away. For instance, the Portuguese were aware of pau-brasil (or firewood) drifting from the west. Columbus, Castile, and luck all converged when they stumbled upon the Americas.

For the Portuguese, finding an alternative route to the spice islands was far less reckless. It took them over a century to circumnavigate Africa, learning gradually and establishing trading posts and outposts along the eastern African coast. Each expedition went a little further. By 1488, they reached the Cape of Storms (later the Cape of Good Hope), and in 1497, Vasco da Gama became the first European to reach India by sea—just five years after Columbus’s voyage.

At that point, for the first time in history, humans had the means to connect all the major landmasses in a way that was both affordable and repeatable. Just 20 years later (1519–1522), the first circumnavigation of the world was completed. For the first time, a human could potentially reach the shores of almost any land within a few years.

In the 15th century, the world changed dramatically due to the technologies and navigational expertise accumulated in the Western world over millennia—coupled with the high cost and demand for spices in Iberia. Within a few decades, the world transitioned from having vast disconnected landmasses to a planet where the first movers—Western Europeans—gained the upper hand. These few kingdoms, and later much of Europe, changed the existing order, wiping out tens of millions of people and cultures in the process, and subjugating nearly every major power on the planet.

That change forever transformed both ends of the lands reached by the Iberians. In the Americas, in less than half a century, a few thousand Europeans—mainly Castilians—overthrew two massive empires ruling tens of millions. In the East, in present-day Malaysia, the Portuguese seized Malacca in 1511 with just 18 ships—then the commercial hub of East Asia. It was the furthest territorial conquest in human history up to that time. To grasp its magnitude: imagine a fleet of advanced vehicles from Malaysia travelling 20,000 km to conquer Rotterdam—Europe’s major transport hub—and controlling it for centuries thereafter. This event had immense geopolitical implications, shifting the balance across Eurasia and reshaping global self-understanding until the present day.

Control of far-flung lands, trade routes, and global connectivity was taken over by small elites from a few North Atlantic coasts. These elites, supported by large home populations, had more resilience than earlier seafarers like the Vikings or Austronesians. Those earlier explorers made equally bold journeys and had the skills and knowledge—but little margin for failure and limited rewards. In contrast, the North Atlantic nations had the means, knowledge, and desire. They could afford the long-distance connection, and more importantly, its coercive and commercial control.

Pandemics, repression, and colonisation enabled long-term European settlement. As Eduardo Galeano famously wrote: “They came with the Bible and we had the land; we blinked, and now we have the Bible and they have the land.”

Previous

Next