What the eight countries that where not fully dominated by the European powers show, is that western powers where obsessed by commerce, or in a formal nomenclature, opening markets. Not in vain this period is know as mercantilism. Even the administrations that more or less escaped direct colonial control were forced to commerce with them, or serve as territories that could be open to the trade routes that crossed them. In all instances, sooner or later, the European powers got their way in and forced the rest of the planet to adopt progressively more European structures, laws, teaching, infrastructure, ways of organizing the territory, their internal affairs, the military, the government, and so on and so forth, culminating in the present day organization of virtually all nations and states on the planet. Even as simple things as having a national flag, a national hymn, is something no nation can escape. Only Nepal has avoided having a square or rectangular flag. The New Zealanders were not allowed to have a Laser Kiwi flag by their own politicians.

Hand in hand of administrative structures, is the administrative terminology. All the nations now talk the same “language”, that of GDP (gross domestic product), unemployment, literacy rate, life expectancy, income per capita, legal system, courts, jails, human rights, commerce treaties, sanitation, health system, infrastructure, mapping, etc.

Many of the areas of life have been completely dominated by Western world practices, organizations, solutions and ways of thinking. This has been accomplished both by forcing the others to adopt these, or by simply efficiency of the scientific and industrial methods that emerged out of the Copernican Revolution initiated by the age of discoveries.

Let us center in one thing that opened the way for all the other administrations to piggyback on this “westernization” and get implanted all over the World. That is the one that started it all, the commerce, or seen in other ways, the exchange markets, the wanting what one does not have and having the means to gain it, be it forcibly, amicably, or in unequal exchange.

As the age of colonization illustrates, there are many ways to go about commencing, but what is common is that curiosity and desire for materials that one community feels it is missing, and the capacity to communicate with the ones that have them. On top of this triad of curiosity, desire, and communication, the European nations imposed European market ways global scales by abusing the superior power of knowledge, technical means, political shabbiness, technology and in some cases sheer luck to overpower the rivals, to the point of annihilation as it happened with the Banda and many native peoples of the Americas. Commerce gone awry results in abuse and, in the worst case, in extinction of the other party to keep access to their material resources. European mentality got to be imposed into a planetary scale, but that was not because of any superior wisdom, but just because of something that we share as humans and make now “humanity” as a global concept, that capacity to have basic communication. Then Europeans exploited it to new levels, to travel, commerce, conquer and ultimately, colonise. Colonisation is no more than the total control of the resources of the land and its peoples.

Lest’s reinforce the idea that commerce was the driver of it all. It was not exploration, it was not even the desire to have more places in the map (although it might play a role, as we will see later), it wasn’t neither the proselytism of many religions and ideologies, it was just the ever increasing complexity that commerce allowed. When peoples where forcibly connected to exchange goods, that made all the other events happen.

Dismantling the Age of Exploration

Let’s first destroy the myth of exploration. What started the globalism movement is the so called “age of discovery” which has already been presented. However, that age of discovery really didn’t discover that much by itself. There was not a sustained desire to “discover”. The places and peoples that were made known to the Europeans was just a secondary outcome of the main motivation, that of the commerce.

That lack of exploratory desire can easily be seen by the desire of Columbus to reach India by a western route, not to see what laid beyond the known waters of the Atlantic. Similarly the Portuguese fueled their exploration of the route to circumnavigate Africa thanks to the commerce of gold and slaves that they encountered when they arrived to Dakar and further beyond, to the Guinean gulf. These preliminary network and exchange routes allowed them to gain the confidence, skills, and interest to do the attempt to Asia. Without that the Portuguese interest to go further south in the almost 100 years that took them to reach Asia would have been lost.

The fact that exploration was not high in the agenda can be easily exemplified by the fact that the Portuguese never “explored” the interior of Africa even though they circumnavigated it for centuries. Hawaii was never “discovered” by the Spaniards, or if they saw it, they never set a foot there, although it was just in the center of their trans pacific galleons voyages from Acapulco to Manila and back. Similarly, Australia’s east was not explored until the end of the XVIII c. although it was jut a bit off from the spice islands. Same, as we have seen, the Bugis never went beyond the areas of western Australia where they could harvest sea cucumber.

These examples and motivations illustrate how exploration was an aforethought of the desire to establish commercial ventures in far away lands. If these could not be commercially viable, i.e. the motivation was not high and the affordability not good enough, then the venture was not pursued.

Dismantling Settler Colonialism

The seeking of material exchanges is further highlighted by the dynamics of the control of the land and of the colonization. Similarly as many lands where not explored, they also where not settled or colonized by the European forces. A good case at hand is the Spaniards. Although they claimed possession of most of the American continent, they never really set forth to control even the first islands where Columbus landed, that is, the Bahamas. Even now, many of the lands of the Americas bear Spanish names, like Guadalupe, a big island in the smaller Antilles. Is not that the spaniards lost its control in a war, is just that they did not even care to keep the possession or minimally defend Guadalupe against other powers. Guadalupe simply was not of interest to them once the initial resources where extinguished these resources where no more than the peoples themselves. Once they where enslaved or forced to work until almost extinction then their interest on the islands was no more.

Fun enough the spaniards where always looking for gold and “el dorado” in the americas. And they never found it, but the big areas of present day Brazil, that later the Portuguese took, had several “el dorados” over the land, just not in the form of a civilization that had already harvest the gold. The gold was in the beds of rivers where the humans that lived around had no interest on it, it had been accumulating by millennia of natural water erosion and sedimentation of the dense metal in the rive beds. Therefore, the spaniards had the tons of gold they where seeking just laying under their foot. Presently, the states of Minas Gerai (general mines, or mines abound in portuguese) and Diamantina (Diamond land), in central-east Brazil, show the gold and diamonds that the Spanish monarchy had under their initial jurisdiction. Similarly in California and Oregon, where the Spanish monarchy had nominal control for almost 300 years, and later the Mexican Empire. But neither mined any river bed, until the US took over.

The spaniards just focusing on either commercing or exploiting the peoples that already exploited the goods they where interested in. We have seen this also in the papuan axe makers, only few groups did the axes, while the rest commerced with them. In the case of the spaniards they first did some exchange, like with Tidore, but soon enough they abused their superiority brought about by their knowledge, technology and the devastating effects that the illnesses that they carried had on most of the local population. The control of the territory through the control of existing administrations can be seen if you check a map of the Spanish empire in the Americas. Their dominions mostly are concentrated in the areas where most of the population lived before their arrival, that is, the Andean region and Mesoamerica. They also had firm control only on the biggest islands of the Caribbean: Cuba, Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. But even Hispaniola western part was eventually controlled by the french, and the fourth biggest island, Jamaica, fell on the hands of the British by 1650. By that point these islands and all of the smaller ones where almost depopulated by the original Tainos, the first people that Columbus’ expedition met. There was not much interest by the spaniards in maintaining a land with no people, that is, no easy means to extract resources, be it by commerce or by force.

Going back to Papua, off shore of Australia and also close to the Maluku spice islands, the interior of Papua and part of its coast was not thoughtfully explored and mapped until 1930, and just because the invention of the aeroplane made it easier the access to these lands. The peoples there had little to commerce with or to exploit at the beginning. Therefore, papuans were left to their own means until the industrialized world sought new resources that where never explored before in an industrial scale, like coal, oil, steel, gas, tin, copper, saltpeter… That way many of the lands of the planet that did not have large administrative centers where left to their own means until the beginning of the XX c. where they where thoughtfully explored, not in search of filling the gaps in our knowledge, but to look for these mineral deposits.

Then, at the end of the XX c. and beginning of the XXI c. the lands that where still almost untouched where reached to exploit a new brand of resources, that of the agrarian production. Nowadays, big areas of pristine forests are falling each second to the hands of humans that want to expand their wealth by the simple exploitation of the production of the soil. The biggest responsible for this new phase of “exploration” of unmapped lands are palm oil, soya and cattle. These commercial products finally are putting a dent into the big tropical jungles that where left mostly untouched by this growing network of connectivity and exploitation. The mighty Amazon jungle is a shadow of itself, with almost half of its surface converted to agrarian land, the same is happening to the formerly lush islands of Borneo, Sumatra and our beloved Papua. And the Congo basing is rapidly joining the club.

The process of accessing the previously disconnected lands came hand in hand with orchastration or simply destruction when their lifestyle or lands where in conflict with the aims of the westerners. That happened often and repeatedly in history, with the clear example with the eradication of many Native Americans in what is now the US and the marginalization of the rest to small reserves in undesired lands.

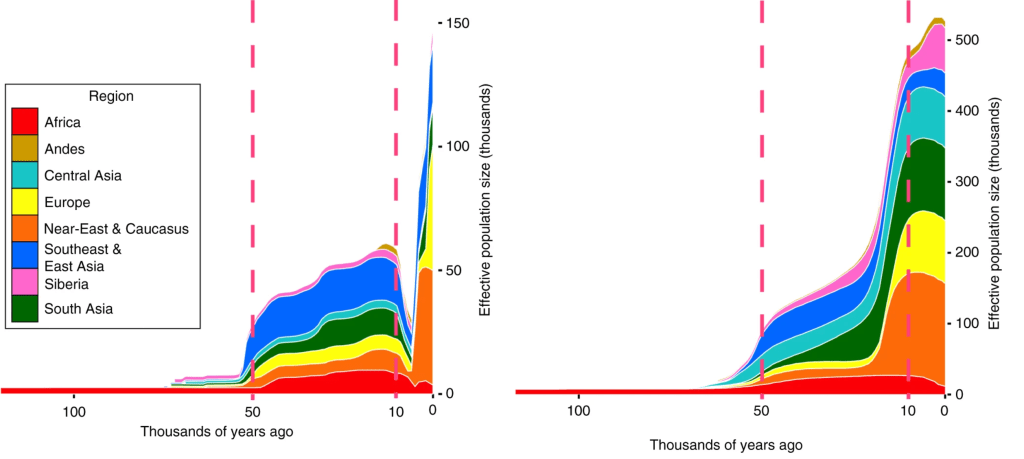

But one can go further back to see this process of taking over lands to be used as a new resource. All around the planet, with the onset of agriculture in each of the different regions of the world, it has been observed that the diversity of Y chromosomes, these carried by men only, was lost by about 90% in a short period of time. That means that of all the male linages that existed on the planet at that time only about one in ten remained, while the rest died out. On the other hand, the diversity of X chromosomes, carried by men and women, remained mostly the same. This happened more or less simultaneously in Eurasia, coinciding with the agriculture there, while in the Americas it happened few thousands of years later, as the onset of agriculture was later and in two different areas, Mesoamerica and the Andres. In Africa it happened later still, by 5000 bc

There are different theories on why this dramatic loss of genetic diversity could had happened, like the grab os lands, active warfare and taking on wives from other bands as slaves, or simply the creation of a male elite that could maintain harems and overbreed the rest of the males over time. However it was, certain linages dominated the genetic landscape and that coincides with the emergence of the big agricultural cultures and later civilizations of the Neolithic. At the same time many hunter-gatherer societies where no longer to be found in many of the lands controlled by the agriculturalists. That points to an ancient clash of cultures, where the ones that where integrated to the agricultural and husbandry networks survived and dominated, while the others where wiped by their neighbors who had adopted a lifestyle different enough from them. Nowadays the world is in danger of repeating the same history in the current global scale, but we will address that, its consequences and possible actions, in another chapter.

The only areas that so far escape a big exploitation are the desserts, Arctic tundra, and the bottom and surface of the oceans. There almost nobody lives, and the affordability of the resources is too high and the cost of the resources there does not compensate it so far in most of the cases.

Dismantling Proselytism

The fact that ideology or religion comes by the hands of commerce should not be of a big surprise, exchange is stablished better with these entities that are similar to the known ones, where more channels of trust can be build. Therefore, the societies that had structures more similar to the known ones for the European world (cities, states, nobility…) where easier to be assimilated to the system.

In the case of proselytism, another area of contact with other peoples and of imposing a common understanding, it also mostly by the hands of commerce. A good example of this connection between commerce and religion spread is the islamization of parts of the Malai peninsula, Indonesian archipelago and Mindanao island from the XVI c. Islam did not spread to these areas at the hands of an invading army or imposed by a ruler. No, the adoption of islam was by the hands of the Muslim dealers that arrived to these shores. The spread of Islam was initially driven by the trade links with the distant lands to their west, especially the species that we have seen. Commercial ventures usually where done or mediated by the local king, or orang kaya. Arab and Indian traders of muslim faith would do better deals with fellow faith followers, therefore the kings and rich peoples had a great incentive to convert, at least nominally, to Islam. That’s how the local rulers become Sultans and sultanates, which exist to this day, like in Brunei. Then the faith would actively or passively percolate to their submits and fellow neighboring lands to integrate them into the commercial network reaching the Spice Islands and their rulers becoming sultans. However, often islam went just as far as the commercial networks. In Halmahera, the big island neighboring the small Tidore and Ternate, even until the XX century the people were believers of their ancestral faiths based on animism and Hinduism. These inland peoples were loosely connected to the commercial networks, therefore there was no strong imperative for religious conversion. Furthermore, many of the Indonesian islands to the east of the spice islands, papua included, and much of the highlands of the bigger islands never converted to Islam, leaving Christian missionaries to proselitise them by the XX century.

Christianity did a similar thing on its own in Northern Europe. When the relationships between the waring bands after the fall of the Western Roman Empire subsided, there was room to establish regular commerce with peoples outside of the formal roman empire. With the commercial networks the Cristian faith came, it took centuries to take hold but eventually much of Scandinavia converted to Christianity. However, less commercially integrated peoples, like the Samis who where neighbors to the Scandinavian peoples, kept their religion until the XIX c

Similarly, the pious spaniards in the americas never went about to evangelize much of the areas that where not under their commercial networks. Many of the forested areas of the Yucatan peninsula and south America where never actively proselytized under the Spanish monarchy, nor where the southern lands of south America, from Tierra del Fuego to Patagonia. These areas where never integrated into dominion or commercial networks until the XX c by the modern American states.

Returning to the specie islands, the preponderance of comenrce over proselitism is sadly ilustrated again by the going tragic legacy of the Banda genocide and extermination. The VOC governor, prior to the extermination asked, repetedly, to their superiors back in Europe to allow him to fight against the locals because “God is with us, and do not draw a conclusion from the preceding failures, because there, in the Indies, something grand can be accomplished” (p47, original in Dutch), grand in the sense of wealth. His religious inclinations where completely oriented to mercantile domination (species monopoly) at the price of the razing of a uniquely distinct population.

Non proselitist religions like Buddhism did have periods of sending missionaries and mass conversion of their population when king Astoga converted to the religion, even sending their own children to Sri Lanka, where Buddhism still traces its roots to that period.

To ilustrate all the avobe cases, a depressing case of a single natural product exposing peoples, —who where until then outside commercial networks– to the cruelty of global markets is natural rubber, or borracha as it is called in Brazil. Until the late 19th century, the Amazon region remained largely uncolonised, but that changed dramatically with the industrial demand for rubber. Natural rubber proved essential for the production of vehicle tyres and the insulation of electric and telegraphic cables—including submarine communication wires, and inspiring Bibendum, Michelin‘s white tyres pile mascot. The Amazon basin was the only region where Hevea brasiliensis, the rubber tree, grew in the wild. Rubber extraction involved “tapping” or cutting into the bark of scattered trees and collecting the latex in small containers, which had to be emptied and processed frequently. However, attempts to plant rubber trees in monoculture plantations failed in the Amazon, as the trees were susceptible to a deadly fungal infection when grown in large monocultures. This biological limitation made wild harvesting the only viable option in the region.

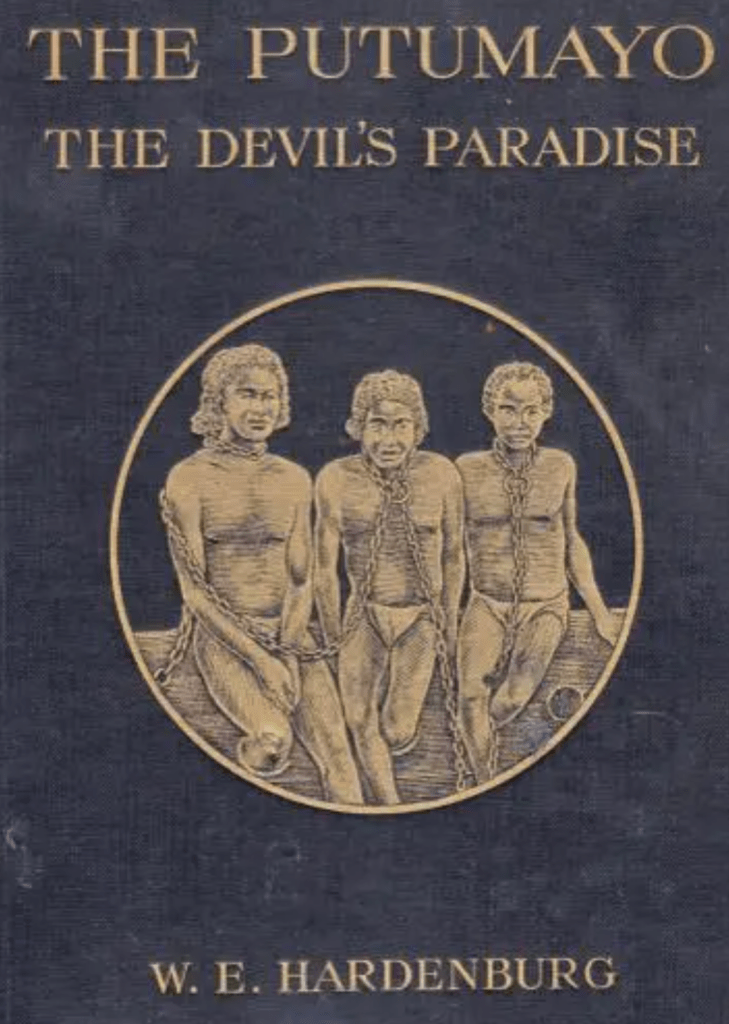

The rubber boom triggered an influx of uncontrolled commercial operators into the Amazon, eager to exploit this monopoly. The most “economical” method of production relied on systematic violence: indigenous populations were enslaved, tortured, mutilated, and forced to traverse the forest, collecting latex from distant trees, with the lives of family at stake.

Men, women, and children were confined in them for days, weeks, and often months. ... Whole families ... were imprisoned—fathers, mothers, and children, and many cases were reported of parents dying thus, either from starvation or from wounds caused by flogging, while their offspring were attached alongside them to watch in misery themselves the dying agonies of their parents. Roger Casement, 1910

They are inhumanly whipped until their bones are exposed and large, raw wounds cover them. They are given no medical treatment, but are left to die, eaten by worms, when they are fed to the chieftains' dogs. They are castrated and mutilated, and their ears, fingers, arms, and legs are cut off. They are tortured with fire and water, and tied up and crucified upside down.Walter Hardenburg, 1912

The trade generated such enormous profits that remote cities like Manaus and Belém boasted European-style opera houses and other symbols of opulence. Yet, this wealth was built on a foundation of brutality—an open secret ignored by the companies, missionaries, and urban populations. Things only began to change when Walter Hardenburg, an US engineer, and Roger Casement, an Irish diplomat and revolutionary, exposed the atrocities to the international community. These reports—fictionalised in the novel El sueño del celta—coincided with another turning point: rubber tree seeds had been successfully smuggled out of the Amazon and cultivated in British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia. The fungal pathogen did not survive the voyage, allowing for large-scale monocultures that drastically lowered production costs. This shift, coupled with global outrage, forced an end to the Amazon rubber monopoly and slightly improved conditions for the surviving indigenous communities.

Similarly to what the British did with ending the nutmeg monopoly, they planted the rubber tree in Malaysia and enforced a policy of prosecution of the abusers of indigenous peoples. As we will see also with slavery, the humanitarian side of it was accompanied by the changing commercial winds, a pattern that we will see repeatedly, and which highlights how much our current world is shaped by the networks, tentacles and shadows of commerce.

The borracha and other examples show that commercial, dominion, and ideological network often went hand in hand, and those that where not part of the commercial networks escaped much of the ideological and political influence. We are seeing that in the case of the Western mentality taking over the world, a link with commercial ventures, be them pacific or aggressive, is a common one. From these examples we can conclude that exploration, colonialism and proselytism are not substantially different than exchange networks —in terms of connectivity. The true real change over time is scale of these networks, with the Western dominions pushing the preexisting connectivity conditions to virtually global scales for the first time in human history. Not that the other themes analysed here did not produce equally or more severe damaging and horrendous outcomes for the peoples affected. What is important to notice is commerce, and maximising profit at the cost of the well-being of everybody else, as one of the main drivers of connectivity, and probably the basis for all the other ones in our current Western dominated world.

From here, we can going back to the current movement of connectivity that was driven by European powers globalisation. With the commerce and greed as a root, we can look at the main frameworks under which this global communication vertebrates. These tools, at times tainted, will be media and mechanisms available to create the concept of humanity, to communicate it to most of human beings, and to ask the question, what does humanity want?

Previous

Next