And as with many things in these writings, it all starts with the French Republic, the first one, or the French Empire, the first one.

But before, we need to go back to the Babylonians, again.

There is evidence that as far as 3,000 years ago, Mesopotamian merchants established a standardised system of weights that later spread across Europe, effectively forming the first known common Afro-Eurasian market. In a study, thousands of objects used as standards of weight over the course of 2,000 years in an area from Ireland to Mesopotamia weighed nearly the same amount — between 8 and 10.5 grams.

This “spontaneous” standardisation, though, started by copying the Mesopotamian standard, called the shekel, which later became a coinage system, and now is the name for Israel’s currency.

In fact, coins are no more than a stamp into a piece of metal to say that such metal is the value that it claims to be, with the purity of the metal that the stamp issuer claims.

Basically, at some point many cultures in antiquity decided that if a certain king or organism put — insert here his or her face, or symbol, or god — onto a round and flat piece of metal, that would be enough for people to believe that such a metal piece was of such-and-such quality and mass. That is why “pound” is both a weight and a coin. It kinda worked because we still have these small pieces of metal going around in almost every place on the planet, with few counterfeit ones, and many, many faces of mostly old — often dead — dudes.

Therefore, the whole system is based on trust that all the coins are made according to the same mass and purity standard, and that such a standard is known by everybody who is using it. We will see more of the importance of trust in later chapters.

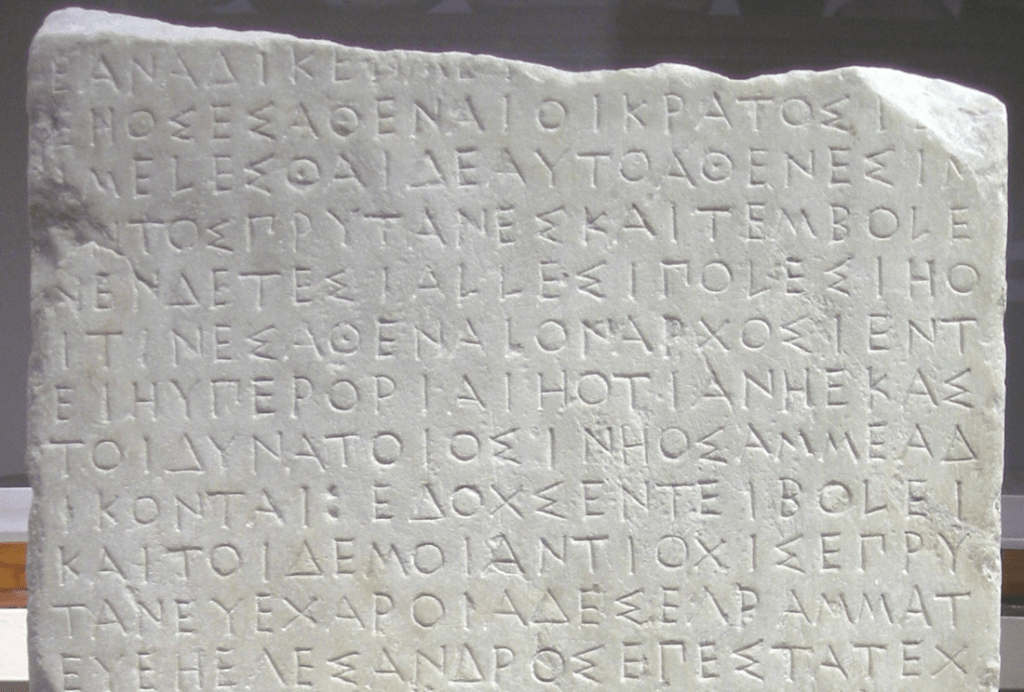

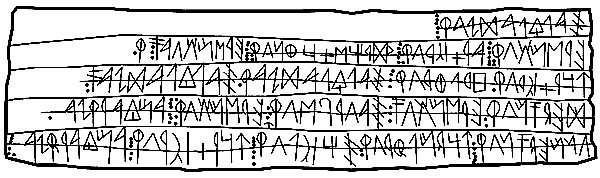

But trust is only needed for the value part of the standard. As we have seen with mathematical and musical notation, punctuation, and francas, a degree of intent and shared interest in communicating, — plus actual political and militaristic control of peoples, and some degree of prestige—, also does the trick, without much need of trust.

But for now, let us jump to the United States now that I am writing this here. Maybe people from the US, and the Myanmar government, do not especially embrace it, but children do not like the Babylonian time keeping much either. Children tend to prefer the legacy of the Republic, the French Republic, the first one.

That is, the metric system. To clarify.

The metric, with a limited set of units that follow a decimal scale, and a conventional nomenclature linking base-10 “words” to multiples (from Greek) — deca, 10, hecto 100, kilo 1000… — and divisions (from Latin) — deci 0.1, centi 0.01, mili 0.001 … — rules the world: the world’s measures (not time; time still is Babylonian, as we have seen).

Compare the French metric to the Babylonian time, with base-60 seconds and minutes, but a 24-hour day, 7-day week, 28- to 31-day months, seasons starting on the 20th or 21st of some months, and years, with some being one day longer than others. Children love to learn the metric, not so much timekeeping.

Before we had a universal measurement system, each yardstick would have a local reference to which it would be computed. For example, going to a marketplace you pour your grain into a container that would tell you how much grain you had and you could sell. Of course that depended on the actual container, and it might change marketplace to marketplace. To this day, I still find some of these containers in market squares set in stone.

But these containers for goods such as grains and olives were not straightforward to describe. For example, for volumes in Catalan-speaking lands we had this:

The quartera was equivalent to the capacity of the container [this container being the one at the market-squares] of the same name. [...]. The aimina is a very old measure that appears in a large number of documents. As submultiples [of the aimaina] there were: the measura, the sester, the cossa, the punyera, the picotí, etc. The barcella was the measure used in the [balearic] islands (where it was divided into 6 almuds or 1/6 of a quartera) and in the Valencian Country (where it was divided into 4 almuds, or 16 quarterons, or 108 mesuretes, equivalent to 1/4 a taleca, or 1/12 of the cafís, or 1/2 fanecà [also the name of a area unit equivalent to 833.3m2, or the land surface that can be cultivated with one faneca of grain ]. The barcella was also used in Tortosa, where it was equal to 3 cutxols, or 6 almuds, or 1/25 of the cafís. For forment [wheat], barley, oats, etc., the cafís is just 25 barcelles [adjusted to the edge of the container]Did you get dizzy with that trainload of measure names, specific for each township or territory AND to which kind of good it was being measured? I did, and is my language.

This system was so complex that a profession, the mostassaf (accountant), was needed to make sure the measures were respected. The mostassaf was a profession inherited from the Muslim muḥtasib, inspector of public places and behaviour in towns. Measurement was, indeed, in need of public behaviour. Muḥtasib comes from ḥisbah, or “accountability”. Interestingly, the term also has both meanings in English: moral accountability, and how to account for economic transactions (the profession being accountant). This connection between debt and morality is deeply explored in — slightly cherry-picked and immensely thought-provoking — David Graeber’s 5000 years of dept. In the Aragonese territories the mostassaf had to keep the original measurement patterns and check that the copies had enough precision with his personal seal for the canes (sticks, length), balances (balance, weights), and all the volume units that we have seen.

What is interesting for the linguistic part is that, although these measures varied from town to town, or mostassaf to mostassaf, they were called the same. So these ‘measures’ were similar enough from one place to the neighbour that everybody agreed for that to be the standard, but not quite. Again, like with languages, the measures might have drifted the further away you went from one place, while the name itself might be the same. As I often heard in India: same same, but different.

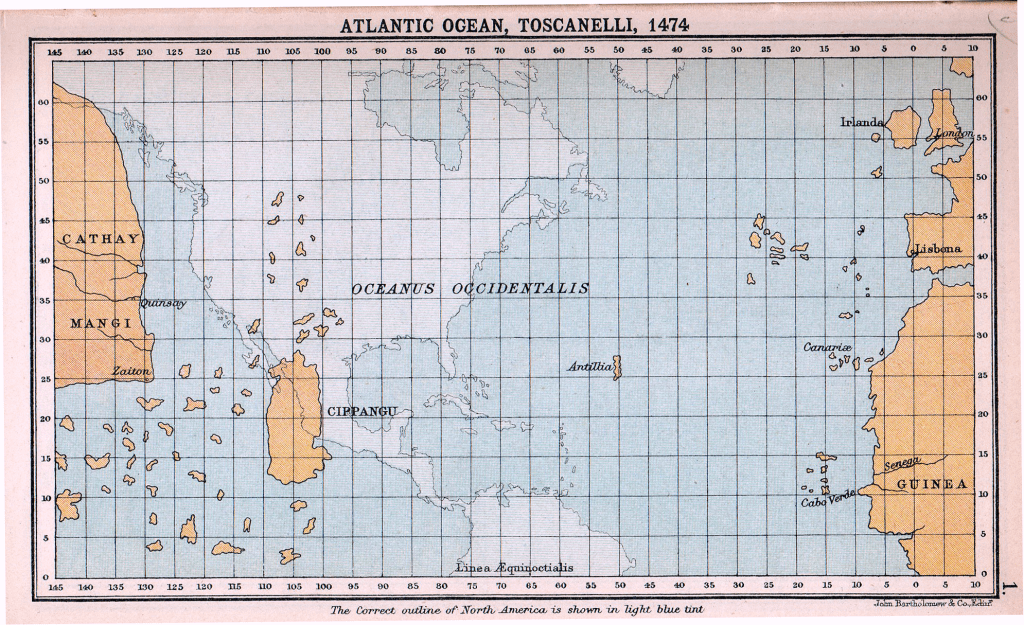

In fact, that same same but different, and terminological mess is one of the reasons why the estimation of the size of the Earth used by Columbus was so wrong.

Part of the computations were using the measurement that Eratosthenes of Alexandria did more than 2,000 years before. His measure was about 252,000 “stadia”. But if I tell you that your dog measures 0.008 stadia, you still would not be sure of how long your dog is. For that you would need to translate it to a measure that you are familiar with. Depending on what the equivalences are, your dog could measure 0.00012 km or 95 inches.

This was the problem faced by Columbus and many of his contemporaries. Nobody really cared to pay anybody to measure, on land, the distance between Alexandria and a place south of it where there was no shadow in a well on an equinox day, the Tropic of Cancer.

These armchair thinkers simply quoted Eratosthenes, and the people who copied him over the millennia. But the Olympic games were long gone, and not many “stadion” existed as a reference. Even today, when we can measure archaeological remains of stadia and historical sources, experts argue that the unit could be anywhere between 150 and 210 metres.

Ptolemy took the lower estimation of Earth’s circumference. Later the Arabs translated previous estimations of the circumference of the Earth by Posidonius, Strabo, Hipparchus, Aryabhata and Pliny. They themselves did some extra measurements lead by Al-Khwarizmi, Al-Biruni and Al-Farghani. All of these translations and new measurements, confusingly, was converted to ‘miles’.

However, naming something the same does not mean it is the same.

‘Miles’ for the Arabs are not the ‘imperial’ ones. Moreover, something that at this point should surprise no one: the mile the arabs where using to translate previous Earth size estimates, and their new measures, has no clear conversion to modern units. An Arab mile from these text being interpreted as anywhere between 1,800 and 2,000 metres. Not so bad but still a 10% margin.

In any case, the same number of miles will be about 1/3 bigger or smaller depending on which mile it is. Same same, but different indeed.

This convoluted process ended up being taken by some people, Columbus among them, to be 25–33% smaller than the modern estimate of about 40,000 km for Earth’s circumference. For convenience, to have funding from inland Castilian monarchs with little experience with seafaring, Columbus took the ‘short yardstick’. Lucky he, and the Castilians, was that there was a continent on the way, just shy of 30% of the total landmass of the planet. Not a small serendipitous crash.

This naming confusion, together with other miscalculations like the size of the Eurasian continent, the distance to Japan from the mainland, and the existence of a mythological ‘Antilla’ island east of Japan, made Columbus pitch that he will reach some land about 4,400 km west of the Canary Islands.

He was off by almost 16,000 km if his aim was to reach the vicinity of Japan!

The Taxing Metric

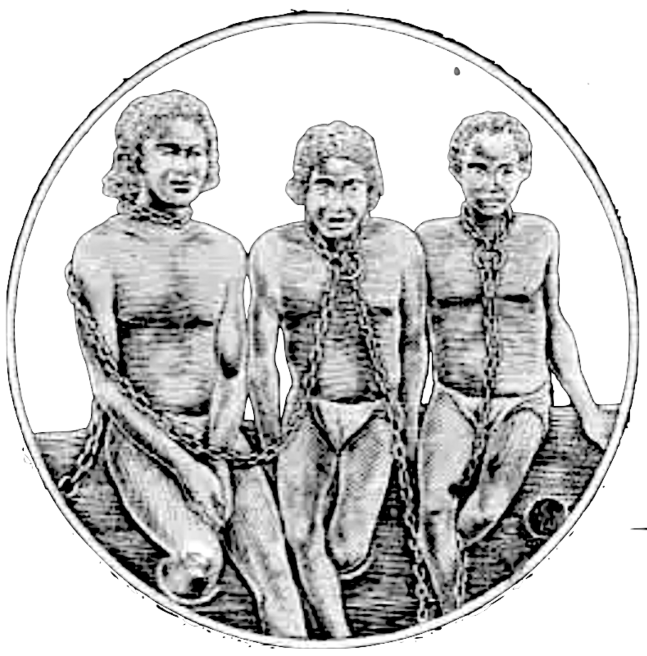

With a continental miscalculation one can see how having universal measurement units helps — unless one has profound ignorance of the continents that exist on the planet to save the day, but condemn, decimate, mutilate and abuse millions of humans who will fall under the administration of that deceiving money-graving person (for more on Columbus’ administration in what was called the ‘Antilles’, modern-day Hispaniola and Cuba, read the reports from his contemporaries).

As transcendental — or not — history-changing Columbus’ blunder and continental serendipity is, this is not the reason for the metric system.

The infamous metric, sadly, comes mainly for taxes, French taxes to be exact.

The metric’s inception was an attempt of unification of measures within France. The kingdom was born out of annexing neighbouring administrations over the centuries, but keeping the local structures mostly intact. Therefore, by the late 18th century it had many different regional measurement systems. The monarchy under King Louis XVI, well on its way to absolutism and centralism, ordered the Academy of Sciences to come up with a unified system. That process was still going on when the Revolution unfolded.

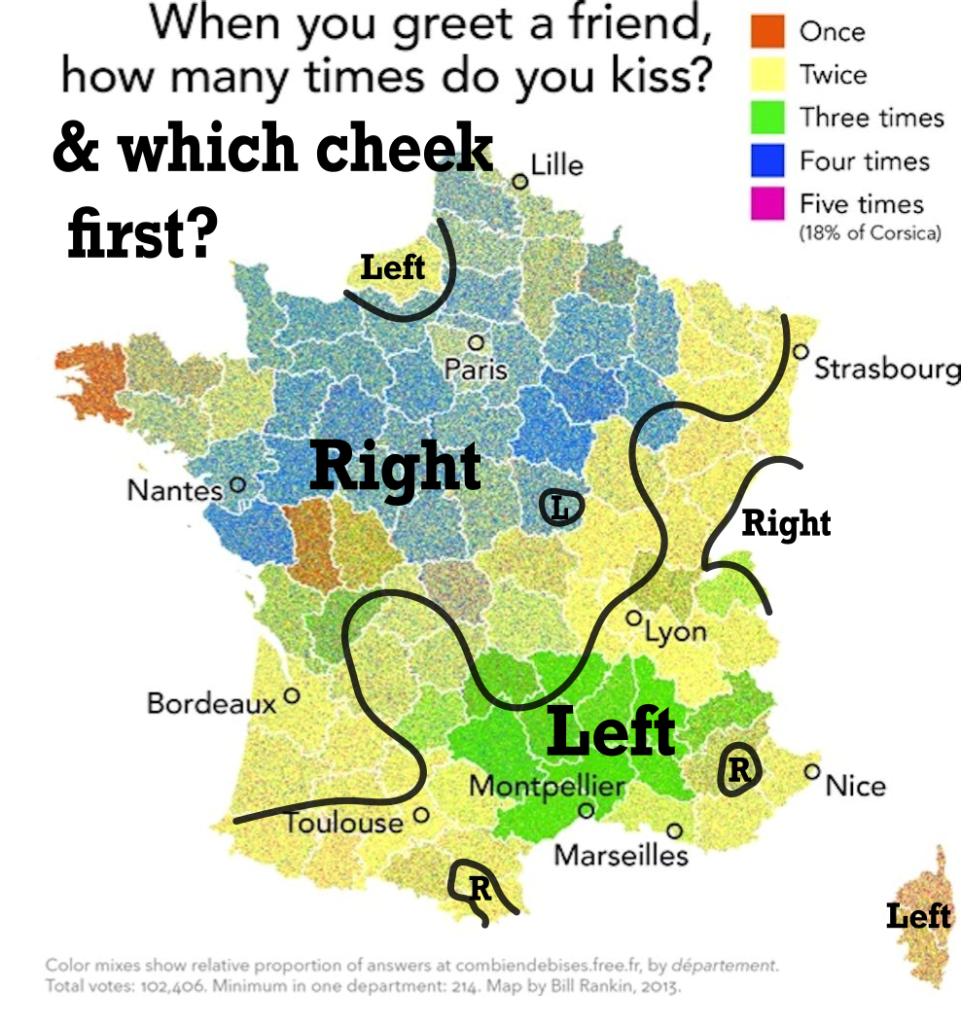

Nowadays, France seems like quite a homogeneous part of the world. Obviously ALL French people wear black-and-white horizontal striped shirts, red-capped berets, are thin and tall, with slim black trousers, both sexes have a spiralling moustache that they continuously apply wax to, making it pointy, while holding a baguette under their arm. While walking, they drink coffee from a delicate porcelain coffee mug sustained only with two fingers.

Beyond exaggerated stereotypes, such clichés just show that such reality is impossible, even more in the case of France.

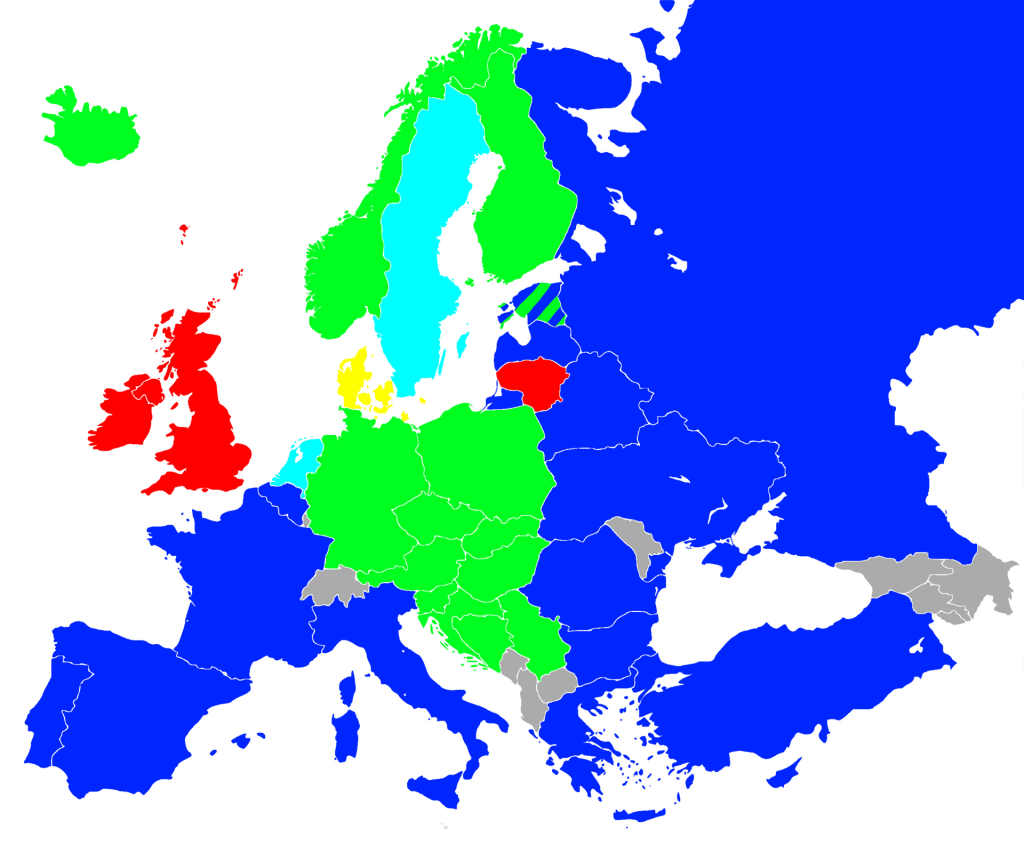

Even today France is one of the most diverse countries in Europe. Up to nine languages are natively spoken there, and its modern borders were not established until after WWII. Moreover, not even kisses are standardised! Depending on which part of the country you are in, you give two, three, or up to four cheek kisses to greet each other. Or you start from the left or right, and these do not even properly overlap (see map).

Adapted from Bill Rankin and Armand Colling (parlez-vous le français?, cheek main direction).

The apparent homogenisation of the metric system actually comes out of that diversity. Citing directly from Wikipedia here:

“on the eve of the Revolution in 1789, the eight hundred or so units of measure in use in France had up to a quarter of a million different definitions because the quantity associated with each unit could differ from town to town, and even from trade to trade […] These variations were promoted by local vested interests, but hindered trade and taxation [20][21].

Notice the taxes there. Paris’ post-1789 administration, but pre-republican, had an evident difficulty to grab taxes. The royal piecemeal system evolved over the centuries as a complex administrative, legislative, and executive mosaic landscape that emerged after the ending of the Western Roman Empire, with the monarch only having token powers in much of the lands it had nominal sovereignty over.

The Sun Kings grabbed more and more power over the 17th and 18th centuries, and, simultaneously, squeezed more the French finances. Finally, in a time pre-revolution when finances were in deep trouble — see the origins of the French Revolution — the need emerged to centralise local measures and make them uniform across the land. That kingdom-wide standardisation would nominally aid commerce and taxation.

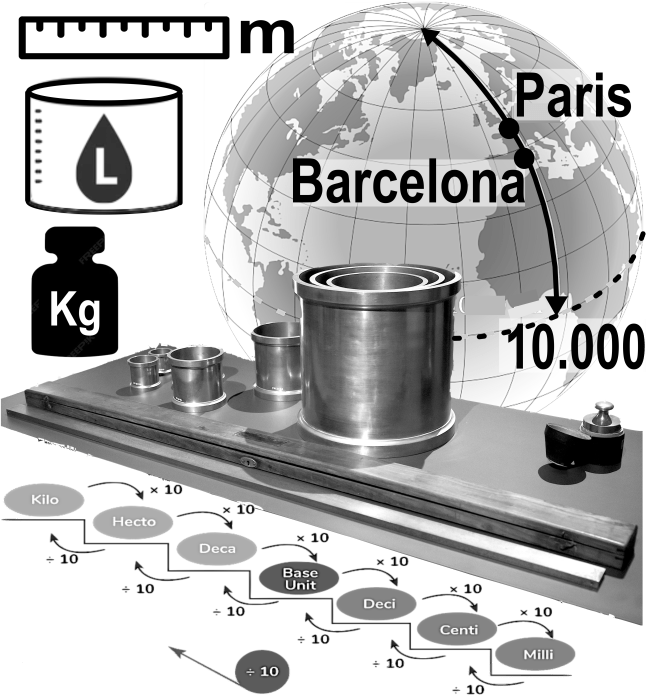

This standardisation started with length. Scientists already wanted to standardise units — we love that; the fun is in figuring things out, not wasting time in conversions. An initial attempt was metro cattolico, from Greek metron (measure), which is the same root as the metric in music: the counting or rhythm of the melody. It also accounts for meteorology, which is the study of the weather, or accounting for weather conditions one particular place experiences — so much rain, so much cold/hot, so much wind, etc. Accountability can be moral or economic, but, it seems, can also be climatic And in some languages, like Spanish, the weather is called el tiempo, or the passing of time, linking change/weather with meteorology again: a tempo. And cattolico is the same sense as the Catholic Church, which simply means universal church, in opposition to others that were not as universal as them. This did not last long, though.

Anyway, the Royal (at that point) académie des sciences decided to base the whole standardisation of measures on the metre. It being a 10,000,000 division of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator following the line that passes through the Paris Observatory, not far from Notre-Dame cathedral. This distance is the Paris meridian arc, at 2°20′14.03″ East. Since this is only ¼ of the circumference of the Earth, the planet has a perimeter of roughly 40,000 km (easy to remember), depending on where you measure it, as it is not a perfectly spherical object but an oblate spheroid.

Moreover, conveniently, the current metre is about two cubits — which is based on human arm length from the tip of the fingers to the elbow — a step (the distance of a human — you know — step), and a yard (the tip of the fingers to the opposite soulder). These length units were widespread in pre-French-Revolutionary Europe, the Mediterranean, and Western Asia.

However, it would not be until 1799 when the current metre was established, and it involves Barcelona, and a lie. Choosing the meridian that crosses the Paris Observatory as the basis of 10,000 km is not only useful for nationalistic reasons. The meridian also allows a long section of land, from sea to sea, in a North–South line in Europe, where distances can be measured with precision, with latitude at each end point, by sea level. The seaside north of Paris is Dunkirk, and to the south the more famous Barcelona. The distance between the two is about 1,075 km, measured by November 1798. The survey manager to the south made an error, estimating the latitude of Barcelona wrong. He remeasured it, but kept it secret. This error would not be disclosed until 1836.

Then académie des sciences used the basis of the metre and water to set the other two standards: weight and volume. The unit of volume shall be that of a cube whose dimensions were a decimal fraction of the unit of length, a.k.a. cubic decimetre, or litre. Then, the weight of distilled water at 0º Celsius (the temperature of melting ice — do not get me started on temperature scales, now that I’m in the US) in that cube shall be, wait for it,

the grave.

(from Latin gravitas, i.e. weight)

This was accepted on 30 March 1791.

They did not like the grave, or the little grave, which they called gravet (one thousandth of a grave). It did not follow the neat deci, centi, mili categorisation — it should have been milligrave. Then, by 1795, already a republic, the national assembly changed the metric unit of weight to gram, from the Byzantine Empire: one twenty-fourth part of an ounce (two oboli) corresponding to about 1.14 modern grams. So kinda convenient, also a similar name to grain (like wheat grain), though 1 gram is about 20 grains.

Then our beloved litre, defined in 1795 as the volume of one cubic decimetre of water at the temperature of melting ice (0 °C). However, since the kilogram was redefined to be the mass of 1 cubic decimetre of water at its densest point at atmospheric pressure (about 4ºC), then the litre and kilogram no longer match. The story is more complex, but we will leave that for the fearful bureaus — coming soon. The word litre comes from the same root as livre (pound), a unit of weight and the name of the French currency until that moment. Again linguistics shows the equivalencies on peoples minds of volume and weight, which make no actual sense, but we are shaped that way.

For much talk of the litre, it is no longer a unit of the International System, but more on that later. It is still indeed part of the metric system, for the division in multiples of ten, and the kilo, deca, deci and other names for the multiples of 10.

In 1795 the republican France was eager to get more standardisation down their belts. Beyond the m, l, kg trio, they got to standardise the are (100 m2) for area, the franc for currency (from France) —s a side note, the currency was the third one to be on base 10, after the US currency and the Russian one — and the stère (1 m3) of firewood (from Greek, stereós, solid, that’s why people take steroids to have solid muscles, not sure if that’s true but I’ll not bother to check). Yeah, firewood needed standardisation. We are asking what does humanity want; apparently back in 1795 they wanted firewood to have a primary unit of standardisation. The world sure changes.

The académie des sciences and the national assembly tried to standardise time too. It would have been decimal: one republican second being 1/100,000 of a day, so bout 0.864 of a Babylonian one, which actually is closer to one human heart beat per republican second, as the heart usually beats a bit faster than once per babylonian second. But we have seen how that went down the drain because the British did better clocks, as we have seen. So much for French vs British clichés and stereotypes.

Beyond seconds’ failure, the metre and weight also failed at the end of the French Empire, the first one. Well, their definitions, to be exact. Because exactitude was the problem.

For the metre, the “Barcelona lie” had been intended to ensure international reproducibility. Who would have thought! This was impractical. So the world lost tourists from all nations coming to Barcelona to measure its latitude and distance to Dunkirk. The city has other issues with tourists, though. Beyond that, the “Barcelona lie” was a small error compared to the “gravitational lie”, i.e. the Earth’s surface has no exact gravity everywhere on its surface, making the planet not a spheroid but a geoid: a kind of potato, a really smooth potato. In actual terms that means that the meridian arc that crosses Paris’ Observatory is about 2 km longer than estimated, so 10.002 kilometres. Or the metre being 0.2 mm shorter than it should be.

In any case, the meridian measure was abandoned and a metal bar held in Paris was the actual definition. We now had a 19th-century French mostassaf. Not a great progress, but at least the units were easy to remember.

For the gram, the “be water, my friend” did not work either.

Humans tend to put our mind into precision once we get a target. The target was universalisation that could be measured. A mass standard made of water was inconvenient and unstable. It depended on the pressure, which was dependent on other measures. Moreover, even pure water is not “pure water” everywhere in the world. Making it “pure” might be difficult if one only wants H2O molecules in it. And beyond being H2O, the ratio of oxygen and hydrogen isotopes (different masses of an atom) is not constant: it might “weigh” differently even though it occupies the same volume.

Therefore, since you already went to the French mostassaf to ask for a copy of a metal bar for the metre, since you were at the door, why not ask for a copy of a kilogram too? Thus, they made a provisional mass standard of the grave, ehem, kilogram.

This was THE metric for much of the beginning of its history, that is, until the fearful bureaus arrived!

Previous

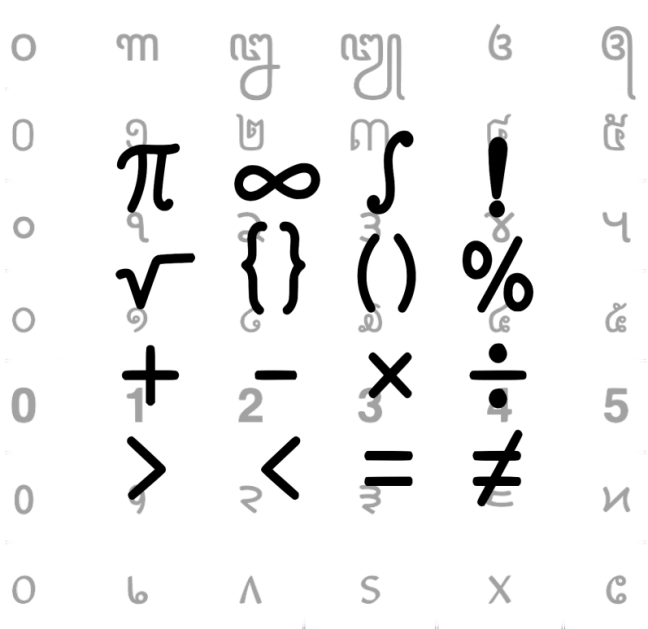

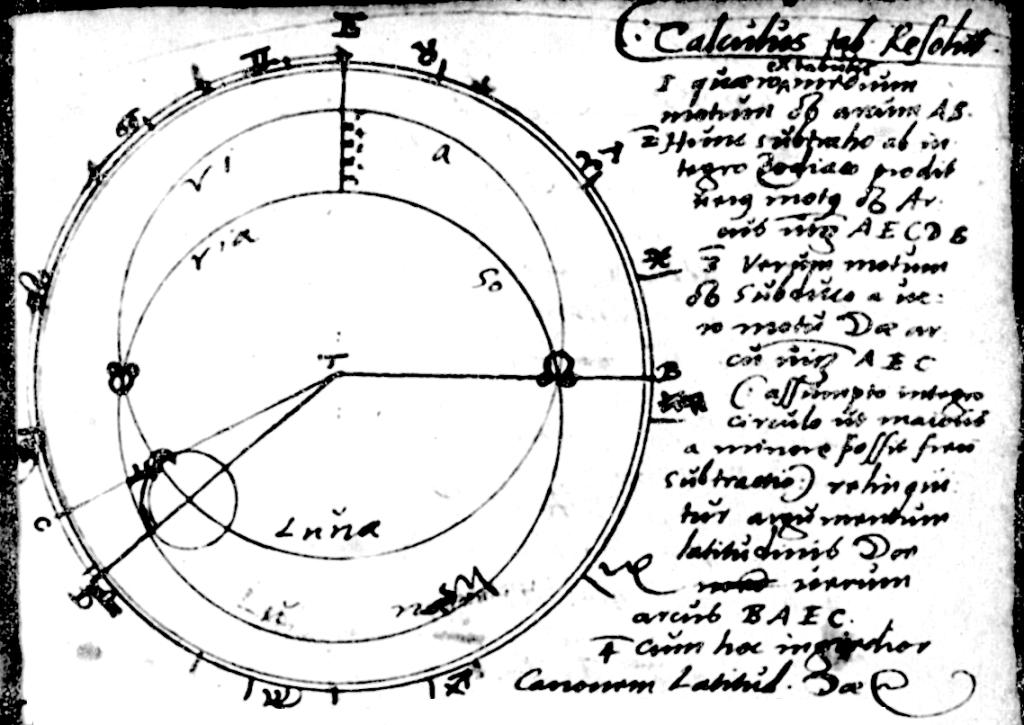

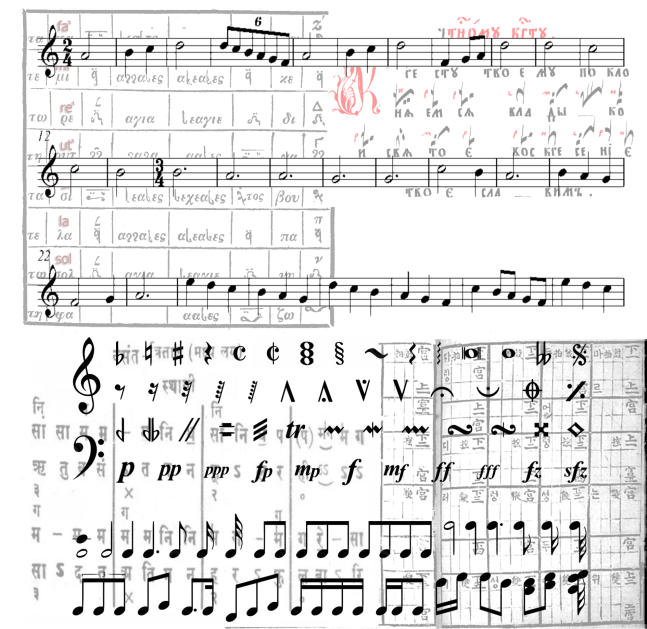

], ‘black’, and ‘round’ musical notes. These symbols, known as ‘neumes’, took longer to standardise; there was still variety until around 1700, but by then most European notation had settled into the familiar form — even recognisable to a musically challenged person like me. Five thin lines, a ‘clef’ symbol at the beginning, and the pleasant ant-like procession of pitch along them. But like mathematics,

], ‘black’, and ‘round’ musical notes. These symbols, known as ‘neumes’, took longer to standardise; there was still variety until around 1700, but by then most European notation had settled into the familiar form — even recognisable to a musically challenged person like me. Five thin lines, a ‘clef’ symbol at the beginning, and the pleasant ant-like procession of pitch along them. But like mathematics,