To keep postponing the Metric, let us explore another metric — the music metric. Since my music ignorance is as immense as music is —and i do deeply apologise to all he music lovers out there— I take metric to mean notation.

As we all know, sound is difficult to record compared to visual signals. Before the invention of gramophones and ceramic disks, the only way to play music created previously was either to have an unbroken sequence of people remembering how to play it, or to encode it in a system that could be reproduced later — either by other humans or by moving machines.

As always, the Greeks and Babylonians (Sumerians, to be exact) had already dealt with the encoding of music, but music is an immensely complicated language, and these scripts were only able to store the strings, the intervals, and tuning parts of the music.

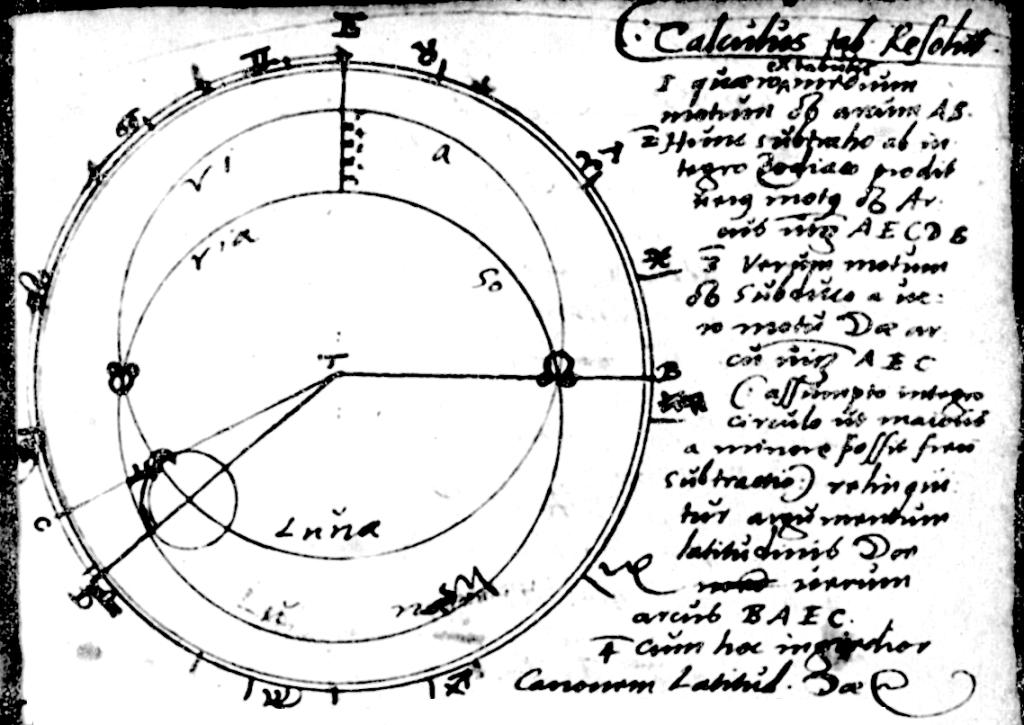

The bit that is often told about the Greeks is the mythical Pythagoras. Beyond his triangles — which mostly were a well-established Egyptian knowledge — the Pythagoreans linked music and ‘harmony’ with mathematics, which they copied from the Babylonians this time. (Interestingly, the Chinese Shí-èr-lǜ scale follows the same logic.) Beyond copying and being attributed things he did not create, Pythagoras did make the musical and mathematical ‘divinity’ a religious sect by the 6th century BCE — if you want to perpetuate nerdy, complex, boring knowledge, you’d better make a religion out of it. In instruments, pitches, notes that were a half or 3/2 apart ‘sounded’ good. With strings, this is related to length, but also tension or tuning. Pythagoras and his followers could not resist giving this a ‘mystical’ meaning, trying to fit existence into his ‘divine’ vision — but reality, as it turned out, had other ideas.

What Pythagoras actually discovered — before wrapping it in mysticism — was that the harmonics of strings resonate with each other, a simple fact of physics that our ears have evolved to enjoy. From what we understand now, it is mostly a coupling of harmonics in strings and “overtones” in general. In other words, when an instrument produces a ‘pitch’, it gives off not just one pure wave but many smaller ones that resonate with it — and these combine to sound harmonious because they complement each other. Then, if you add another tone that also resonates with the primary frequency, or some of the overtones, that is also harmonious.

Our auditory system also resonates with nearby frequencies, which is why we find it oddly unsettling when two notes are almost — but not quite — the same. And there is a cultural layer on top. If you hear something that is slightly dissonant often enough, it will “sound good enough” not to care. It’s only when we hear music from another culture — one that divides its scales differently, using another temperament — that we start to notice those dissonances. Once your ear adjusts to the new metric, returning to the old one feels oddly off for a while.

And again, we go to Western Europe to observe the origins of most modern music notation. In this case, it started with the singing of prayers. As you can notice, voice is a continuum; there is no predefined ‘do’ or ‘re’. So voice, and music, had to be discretised into common units that everybody could ‘aspire’ to. This standardisation, inspired by the mathematical spirit of universality, was thought to be divine — which made following Pythagoras rather straightforward. Until it wasn’t (but more on that later).

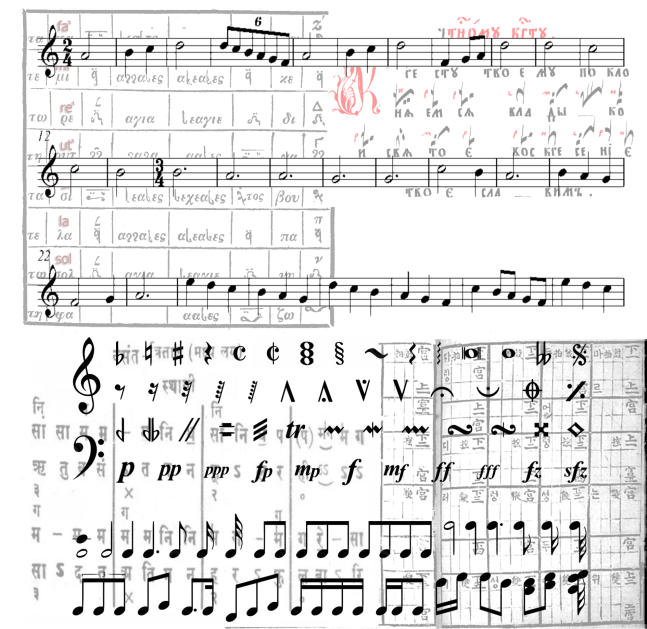

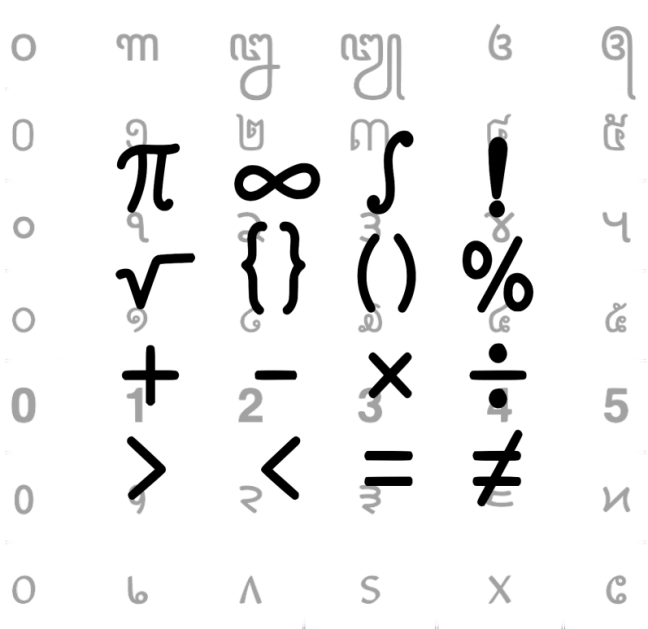

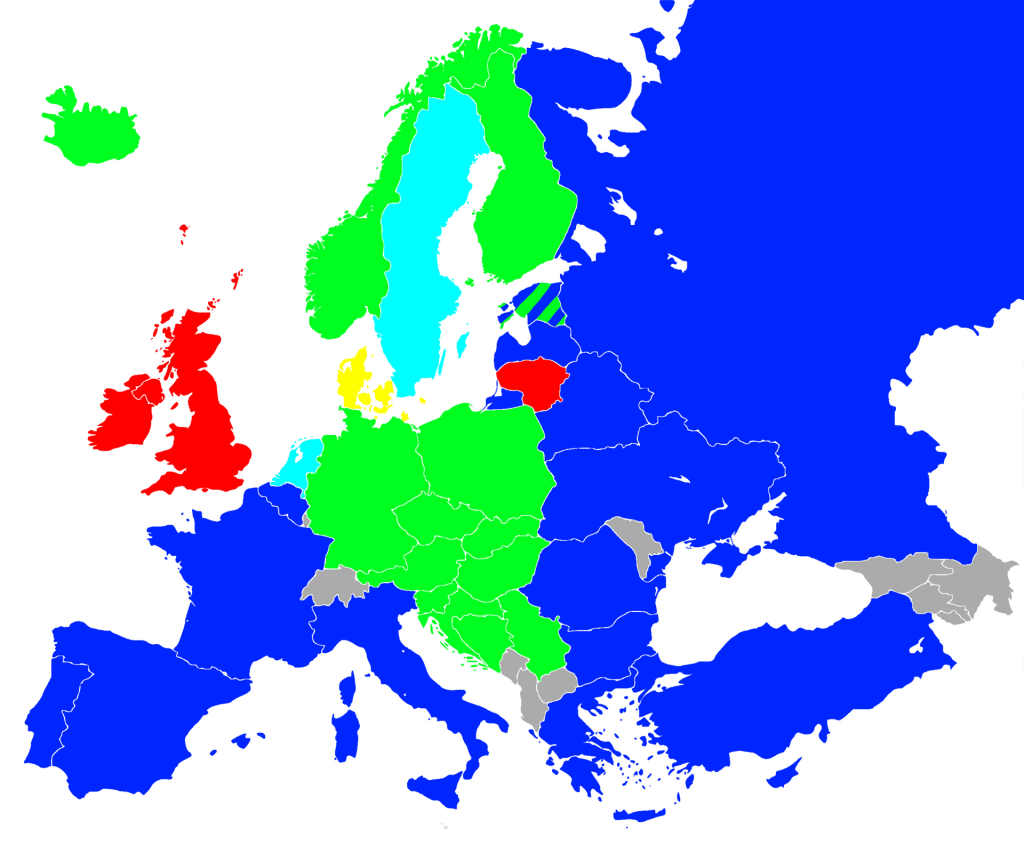

Before the well-known pitch system, what ecclesiastical choruses did by the 10th century was to annotate when the melody went ‘up’ or ‘down’ on top of the lyrics. Then a reference line was added to show the relative high and low of the melody. From there, by the 11th century, more lines were added above and below to structure the pitches in a standardised way. In parallel, it was necessary to know what the actual ‘pitch’ was, and that’s where the same guy who started adding the extra lines developed solmisation, with the familiar Do–Re–Mi–Fa–Sol–La–Ti (or Si) sequence appearing (though Ut instead of Do). This provided seven basic notes, which mirrored pre-existing scales like the Byzantine Pa–Vu–Ga–Di–Ke–Zo–Ni and the Indian svaras Sa–Re–Ga–Ma–Pa–Dha–Ni. This naming (blue in map below), however, was never fully standardised: the British preferred C–D–E–F–G–A–B (red in the map), as in guitar chords (E–A–D–G–B), while Germans and neighbouring regions (green, yellow, and sky blue in the map) used C–D–E–F–G–A–H.

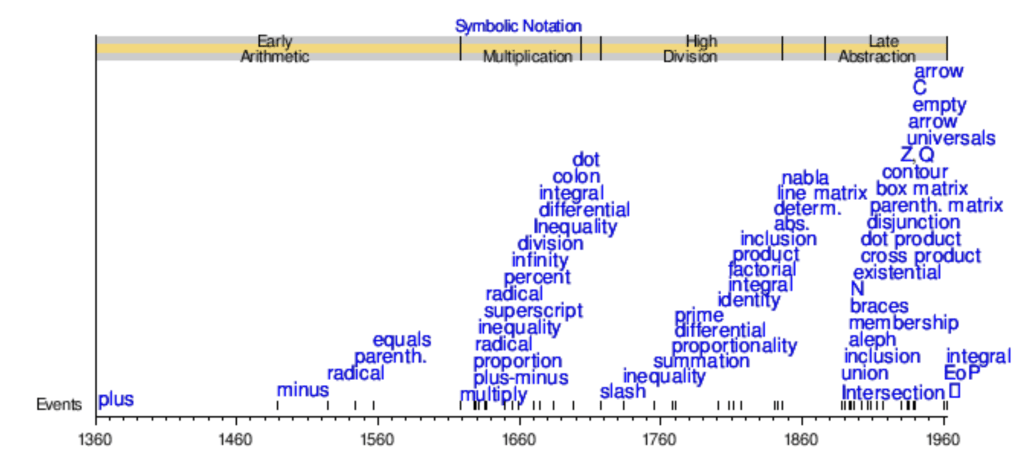

If one doubles around the central note, this provides the conventional twelve notes to be placed on top of the five-line staff developed by the 13th century. If you place a symbol on top of the five lines, plus four in between them, and two more on top and bottom, you have eleven spots; adding one more small line (a ledger line) at the bottom when needed is easy and gives the Babylonian twelve. At this point, we have something that looks a lot like the modern musical staff, or pentagram, and symbols that look a bit like the familiar ‘white’ [ ], ‘black’, and ‘round’ musical notes. These symbols, known as ‘neumes’, took longer to standardise; there was still variety until around 1700, but by then most European notation had settled into the familiar form — even recognisable to a musically challenged person like me. Five thin lines, a ‘clef’ symbol at the beginning, and the pleasant ant-like procession of pitch along them. But like mathematics, musical notation is immense!

], ‘black’, and ‘round’ musical notes. These symbols, known as ‘neumes’, took longer to standardise; there was still variety until around 1700, but by then most European notation had settled into the familiar form — even recognisable to a musically challenged person like me. Five thin lines, a ‘clef’ symbol at the beginning, and the pleasant ant-like procession of pitch along them. But like mathematics, musical notation is immense!

For the temperament, or tuning itself, Pythagorean (Babylonian and Chinese) fixing of the twelve notes to perfect ratios of 1/2, 3/2, 2/3 and their powers (C 1⁄1, D 9⁄8, E 81⁄64, F 4⁄3, G 3⁄2, A 27⁄16, B 243⁄128, C 2⁄1) failed because, contrary to belief, some of these pitches do not sound harmonious when played together — particularly something called the Wolf interval. It also made it difficult to shift the scale up or down beyond the twelve notes, since the spacing between them was uneven. To solve this, particularly for string instruments with many keys, like the piano, equal temperament became the standard by the 18th century, in which the distance between notes is, as the name suggests, equal. Developed independently in Europe and China in the 16th century, in mathematical terms each frequency interval is 1/12 of the octave (the distance between the highest pitch and the lowest), and the ratio between consecutive intervals is $^{12}\sqrt2$ — all equal in a logarithmic scale.

There is much more to it than that, and music notation and temperament have been evolving ever since, not unlike mathematics, with hundreds of signs emerging. Moreover, other familiar notations like the C–D–E–F–G–A–B guitar chords are ever-present. And music notation beyond the Western one is rich and diverse. But acknowledging my immense ignorance of music — and the fact that the basics have been quite established and spread around the world — I will limit myself to this standard that, like mathematical notation beyond numerals, has taken over the world.

From then — plus a few more inventions in tuning, non–string-pipe instruments, and electronic music among others — we have the fascinating fact that music written in one period can be played by future or distant musicians who have never heard it, as long as they possess the relevant knowledge and skill.

That transfer of sound into visual form (and back) is a truly fascinating invention — a collective effort across generations showing how sensory experience can be encoded, standardised, shared, and reinterpreted again and again. And, for better or worse, this very standardisation enables immense creativity while also stifling non-standard forms — a kind of ‘Western’ myopia, or more aptly, tone-deafness.

Thus, to recount: by the year 1800, and to this day, we have the following global or quasi-global standards — timekeeping, the calendar, mathematical notation, the Copernican principle, music notation, and temperament. These are not that many, but we will see that the other topics introduced — commerce and francas — will play a dominant role in the following two centuries.

Plus the infamous metric system! Nobody expects the metric system.

Prebious

Next